1 I started writing this piece in September. Tabled it, like 30-some others in my “drafts” file, for whatever reason. Some of the original I’m retaining, but not all that much, because, hey—a dude whacked a healthcare CEO in broad daylight.

It started like this…

I once knew a guy named “Bing” Bengtson.

He was a hoot, and admirable. He lived with his wife in a small house where every year he coached kids competing in the local Optimist Club Oratorical contest. Twerps, nerds, and misfits like me would get steered to Bing in the hopes of winning a scholarship if we were extremely lucky (a whole grand if we won something like three levels of competition back then…I don’t know if they’ve adjusted for college cost inflation, but this amount might just cover three textbooks these days).

We’d gather once a week at Bing’s place and sit on the floor of his living room while we worked on our speeches and gave progress reports, learned the rules and norms and rehearsed and timed our presentations. I got to know one of my coolest friends through that rhetorical exercise, and I ended up winning that scholarship in Kansas.

Anyhow, Bing was, at the time, approximately seven thousand years old, or so it seemed to us kids, and he was a font of folksy turns of phrase. The one that stuck with me was his ultimate expression of contempt for a person: “He’s not worth the bullet it would take to blow him to thunder.”

I loved the “thunder” part. Bing—the veteran of Toastmasters and trainer of generations of Optimist Orators going back to the days of Biblical patriarchs—would never dream of swearing in front of young people. Not even so much as to say “hell.”

I think of Bing’s expression a lot. Maybe it’s the world today. Maybe it’s North Carolina Lieutenant Governor Marc Robinson’s least outrageous statement, that “Some people just need killing.” Maybe it’s the two assassination attempts (were they?) on Donald Trump. Maybe it’s the spectacle of so much world-shaking lawbreaking only to be met by glacial tip-toeing of legal procedures, followed by blatant interference by the powerful to shield and provide immunity for those we watched in real-time do the crimes. Maybe it’s the execution of Marcellus Williams in Missouri and the quiet retreat from opposition to the death penalty by the Democrats—although, it must be noted, the three decent SCOTUS judges wanted to keep Williams alive.

Maybe it’s the casual, cynical under-bus-throwing of so, so many human beings in rapid-fire, news-cycle succession. It’s still September, folks, and the Springfield, Ohio, attempted pogrom of stochastic terrorism promoted by the leaders of one of America’s two viable political parties has run it’s entire life cycle in the past two or three weeks, if you can believe it.

Whatever the cause, I think on Bing’s bon mot (mal mot? I don’t truck with French) often. There’s a weakness in all of us, I think, the yearning to reach for simple answers, and frankly, just shooting the bad guys is a simple answer Hollywood has offered us ever since I was a kid watching westerns on black-and-white sets we’d get because some neighbor upgraded to color and gave us their old one.

I try not to push the temptation of just shooting the bad guys too far away. I believe in temptation. Mark Twain taught me that. His “The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg” tells of a stuffy, stick-up-the-ass town where everybody is raised to believe they’re the most moral, the most honest, the most virtuous citizens around, and they proudly wave that flag.

Of course, it’s Twain, so they’re really all hypocrites who entertain their own prolific private vices and petty hates: they’ve just taught themselves to deny that such exist. Spoiler Alert: The town screws over a stranger who plots and enacts his revenge: by placing before the hamlet a big ol’ honking temptation that none of them can resist. They can’t resist it because they have no practice in resisting temptation. All the petty vices they indulge on the daily are whitewashed and rationalized away as normal or even virtuous thanks to their programming as people who couldn’t possibly do such things, the good people, the “very fine people” we might say today. Because they cannot conceive of themselves as capable of wrong, they cannot practice conscious resistance to temptations when they occur.

Which is to say, they cannot reject those temptations using the very morals they claim to hold. If Aristotle was right that virtue is a habit, then the town’s inability to regularly practice resisting temptation (because they believe in their inherent herd immunity to it) deprives them of the opportunity to develop the habit of developing virtue.

That is why I think a lot about Bing’s comment about “blowing people to thunder,” and it’s why I often—pretty damn often, frankly—quasi-fantasize about all the dark “jokes” about guillotining the ruling class, eating the rich, putting Elon Musk “up against the wall.”

Yep. The thought of just plain whacking people who I tend to believe deserve it runs through my mind a lot.2 I let it. It’s a temptation, at least a temptation of thought, of ethical reasoning.

And I continue to reject it.

Or well, if not reject it, per se, then at least I let it drop with a sigh, because I can’t ever convince myself that it’s completely justifiable or workable. It’s like a tempting side route, a shortcut. But I know from looking at maps a million times that it dead-ends, no matter how satisfying the scenery might be, no matter how much time it may promise to shave off the journey.

But I believe it’s important to keep seeing the sign for the shortcut, beckoning.

It’s like those scenes in TV shows where the long-time sober recovering alcoholic orders one drink at the bar, then sits with it before him and stares at it, not imbibing. He knows he can drink it. He tests his willpower, or he reviews all the reasons and commitments he has made, runs through his life for all the lessons and shameful memories that tell him why he shouldn’t drink it.

Last night, I finished the recaps of the oral arguments in United States v. Skrmetti, the case challenging the sweeping ban of gender affirming care for minors in Tennessee, now before the Supreme Court.

Back in the Bostock decision, the Court ruled that you can’t summarily fire people for being trans because it’s inherently sex discrimination: what you’re doing is making assumptions about what’s appropriate for a person based on ideas of a gender role you assign to a sex. If a straight man dates women, and you’re cool with that, but a gay man dates other men, and you fire him for it, you’re importing and imposing your beliefs about gender roles (“what’s proper for men to do”) onto the man’s sex. If a cis woman wears a dress to work and you don’t bat an eye, but if a trans woman wears a dress to work and you freak out, it’s because you’re imposing your beliefs about gender roles onto her sex assigned at birth. You can’t escape or get around the fact that you are making assumptions and imposing some beliefs about what’s “proper” for the sexes to be doing and thus, treating the sexes differently.

This should have been the end of it. But Bostock was technically, legally, about Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Skrmetti case is technically, legally, about the Equal Protection Clause, so we have to do this fucking song and dance all over again, even though the logic of the discrimination analysis is precisely the same.

In Tennessee, minors are banned from gender affirming care only if it’s inconsistent with their assigned sex at birth. So, if you’re a cis boy with a squeaky voice and delayed puberty who gets beat up relentlessly by the neighborhood shitheads, it’s perfectly legal and acceptable to take some hormones to deepen your voice and accelerate your “manliness” progression. But if you’re trans and utterly miserable, depressed and dysphoric, knowing that you are really a boy despite the entire world treating you like a girl, you can’t legally get access to the same hormones to deepen your voice or delay further development of your body in a direction that may well torment and horrify you.

A doctor asked to prescribe these drugs literally cannot know if it’s legal to do so if the patient appeared behind a screen, for example. The doctor would literally have to know “what was in the patient’s pants.” Same drugs, but legality depends on sex and what the Tennessee legislature believes is appropriate for each sex to do and be and be like.

So advocates Chase Strangio, representing the ACLU, and US Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar laid all this out, and the three decent SCOTUS judges instantly got it. It was a slam dunk.

Neil frickin’ Gorsuch wrote the Bostock decision, so he should be a gimme, but no one knows.

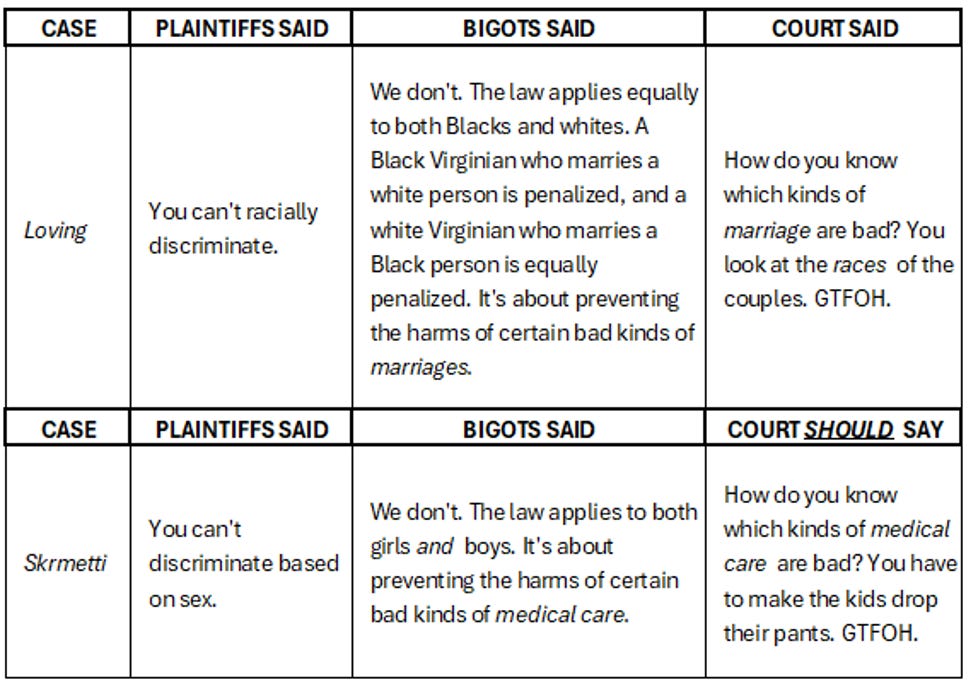

Clarence Thomas, who is Black, is married to a white insurrectionist woman named Ginny, and that union is possible largely due to a case called Loving v. Virginia (only a couple years older than I am). In Loving, the Court looked at a bunch of anti-“miscegenation” laws based on pseudo-science claims that racial intermixing was harmful (very much like the pseudo-science behind the claims that gender affirming care for minors is harmful) and said, “Even if these are true, it doesn’t matter: you can’t do that kind of discrimination, fuckos.” Worse still, Tennessee’s arguments in the Skrmetti case kinda boil down to the same exact bullshit used in Loving:

So the law, the precedents, the facts and evidence, the text of Tennessee’s own statute, the logic of Gorsuch’s own prior decision, the logic of the decision that allows the Thomases to RV across these United States without going to jail—all show Tennessee is just bullying the shit out of an incredibly tiny minority of children and their supportive families.

And yet it’s highly likely the SCOTUS Six will just ignore all that and impose suffering because they fucking can. They can get away with it. They’re untouchable. Unaccountable. They literally need not “give an account” of their decision that accords with any of the principles or logics or evidence—all the things our vaunted justice system is supposed to be bound by. They’ll just slap together some nonsense that contradicts itself on its face, and the dissenters will point that out, but it’s so esoteric and legalistic and followed by so few in such elite circles, on behalf of such a tiny minority, whose fates seem so unconnected to ours (though that’s so incredibly false), that it’ll slide away from public consciousness like all the other body blows this court has delivered.

You do everything right, according to the rules they set up, the rules they say you have to follow, and because they have all the power, they just overrule you, and even though you knew all along it was just a naked power game, you bit your tongue til you could barely speak anymore and played along because that’s how you’re supposed to do things as a good American, a good person, a good Christian or whatever…and it’s not that things don’t get better or don’t get better fast enough…things get rapidly, viciously worse for the weakest, most vulnerable people out there.

So this week, when a hooded gunman just up-and-whacked UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in the lobby of a New York hotel, I was mildly surprised.

Surprised that he pulled it off. Surprised that Thompson was such an entitled dipshit that he didn’t already have so many ex-Mossad mercs in a cordon around him that he’d make drug cartel lords look like pikers. I mean, the dude headed one of the worst offenders out there in terms of systemic, structural violence.

And that’s the rub. Structural violence. The routine, expected, known and arguably intended violence, suffering, and death produced by the systems we’ve created or allowed to be created through indifference and inattention and ignorance.

Not all of us, of course. Some of us rail and fight and advocate against such violence and structures, only to get dismissed as radicals or socialists or utopians or crazies. Because the way the world works seems so inevitable,3 so entrenched, to some, so normal and so virtuous.

I know absolutely nothing about this dead CEO. On purpose. He probably loved his wife and kids. He was probably fond of any pets he had. Statistically, it all seems likely. Then, too, there are statistics about the lopsided presence of clinical sociopaths in positions like…CEO. And the thousands upon thousands of people who suffered and/or died thanks to his company’s denials are also statistically likely to have loved their families and pets, so, there’s that—and suddenly we’re back to math.

Google the phrase “guns as equalizers” and just scroll through the results, which are mostly from second-amendment fetishists. But they’re not entirely wrong here: if we build systems that metastasize and eat us, with no meaningful recourse for the vast pools of essentially powerless individuals out here, well, we do have a shitload of guns—thanks to a system we built and allowed to metastasize and eat us. As Franchesca Ramsey likes to sing, the leopards tend to eat faces, folks.

All you need are people who just don’t care anymore. People who have given up.

Arrested as I tried to revise this: Luigi Mangione, from what folks can tell, a surprising candidate for hitman. No bets on whether this will be made into a movie; only bets allowed are when it will hit streamers and theaters. His reading taste seems indiscriminate, leaning toward “mark” for hucksters. His family is a sprawling Catholic Baltimore clan, connected to local-state money and politics, a cousin (at least) an elected MAGA assemblyman. His tweets and politics, from what I hear, seem a mess of Unabomber manifesto appreciation, some Jordan Peterson and other weird, tech-striver-midbrow-airport-book eclecticism.

I don’t knock eclecticism. I don’t even knock youth, which is what the hoodied gunman’s pictures screamed at me, and why I worried about the whole discourse. To me, the guy looked, like, 19, but then everybody not blatantly 40+ looks around 19, so that matters not at all.

My point is, my ability to parasocially, or aspirationally, or folk-heroically project onto the gunman was limited by the fact that he was obviously very young in my eyes. That meant he was still a-forming. That meant it was not all that likely he was coming from a place like mine: the weathered crag worn down by erosions and having read a lot more books and seen more history and participated in the discourse around it in real time. The odds that this kid was a real “Robin Hoodie” as some called him, an enlightened champion of the down-and-out oppressed masses with a fully-formed politics that I could Amen would have required him to have emerged, full-grown, from the head of Marx or something. Not impossible, but unlikely.

Look: I’m a weird mixture of influences and values. I tend to think most folks are. I know which ones I prefer, which ones I consciously try to gravitate to, which ones I try to will into being. But I don’t deny that there’s a mix.

Cognitive linguist George Lakoff might call me a little “biconceptual.” Cartoonists might depict me with an angelic mini-me on one shoulder and a devilish avatar on the other. The Indigo Girls sang,

Everything that I believe / crawls from underneath the street

Everything I truly love / comes from somewhere high above

Everything that I believe / is wrong with you, is wrong with me

Everything I truly love / I love in you and I love in me.4

audre lorde is over here reminding me that “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house,” and I’m like, “Well, they might tear it to smoking husks of rubble, but you’re right: they certainly won’t build the people’s house we desire.”

A.R. Moxon, whose efforts I admire, writes things like, “Every human being is a unique and irreplaceable work of art carrying intrinsic and unsurpassable worth.” Yet I have one helluva time becoming outraged over the hoodied gunman killing the insurance CEO.

Mostly, I’m indifferent, and that’s not…great.

Why am I indifferent? Because as high up as Brian Thompson was in his company, he’s still just an individual, just a cog in the structure. He’ll be replaced by somebody new whose job it will also be to maximize shareholder value by reducing costs (payouts, coverage) for people needing medical care, using any means necessary, legal or not so much. This is what a “good” CEO does in the structure, what makes a company a “good” investment vehicle.

Thompson himself did not personally direct each and every operator to deny each claim they denied; he presided over a structure that incentivized denials, and that was his job. He was, presumably, playing by the rules, raking in acclaim and reward for doing a “good” job. If he’d been visited by three ghosts one night who scared him into growing a conscience, went to work the next day and announced a complete set of policy reforms to reverse course for his company’s entire business model, he would have been fired and possibly sued into bankruptcy, then become unemployable in his industry. He would have become a “bad” guy, a pariah in the system.

That system is what should be assassinated, let’s be perfectly clear here. That system is evil and inhumane and dehumanizing and morally wrong and murderous.

I believe people who hold as Moxon does would build a system where the basic needs of everyone are met. One can come to this from a religious perspective. I try to come to it from a humanist one now that religion is more or less closed to me. I try to remember that each person is that “unique and irreplaceable work of art carrying intrinsic and unsurpassable worth.”

But then I look at perpetrators of great systemic violence. By definition, these folks are powerful and either know what they’re doing or damn well should know. Power thus becomes a huge caveat to my otherwise humanistic and dignitarian aspirations: “It’s wrong to just shoot people…Okay, but is it really? Like, what if they are immensely powerful, structurally murderous motherfuckers?” I mean, that’s the question behind assassinating Hitler, right? Or time-traveling back to suffocate Baby Hitler.

So the question always presents itself, if a human life is imbued with “unsurpassable worth,” can that value ever be alienated? Moxon says this worth is intrinsic, but that could just mean basic, inherent, inseparable from. So immense value and worth is inseparable from human personhood. Asked and answered.

Well, not so fast.

Because now we go to the question of whether or not humanity or personhood can be alienated, can be given up, sold or traded away. Don’t be so quick to dismiss: there’s a long tradition of stories of folks who “sell their souls” to various devils and thus trade away some vital and precious birthright of virtue and hope and blessedness for a mess of pottage. That notion is embedded in our cultural mythos. Can I give up what makes me human, what makes me a full person? What might that key thing be?

If I surrender my own agency, my freedom to choose right from wrong, by surrendering to a system that dictates my actions—am I surrendering something fundamental that makes me human, or a person? Can a person deprived of freedoms be considered a fully accountable human person?

These aren’t utterly bullshit questions. We ask something like them in courtrooms when assessing responsibility for crimes. We asked it in the Nuremberg trials, and nobody claimed that Eichmann personally exterminated a single Jew. More relevantly, we hear choruses sing such themes on the topic of…capital punishment: that heinous crimes signal the loss of dignitarian right to not just freedom but life, often because the perpetrator has “proven” through action that he or she is no longer fully human and “worthy” of continued existence.

…or so says the tiny figure on one shoulder, gesturing sternly with Nick Cave’s red right hand.

Against this comes the opposing advocate, who demands to know “Who TF are you to decide?” He might quote Gandalf’s Christological reminder:

Many that live deserve death. And some that die deserve life. Can you give it to them? Then do not be too eager to deal out death in judgement. For even the very wise cannot see all ends.

Maybe the kinder imp next to my ear hands me a stone, asking if I’ll be the first to cast it, doing the head-tilt-raised-eyebrow thing to remind me of all the times I, too, was a shitty person who caused harm to others or surrendered my own fundamental or signature capacities of human personhood, whatever they might be. To my knowledge, I never caused any deaths or prevented sick people from getting needed medical care, but we all bang into each other and wound others, and not always by accident.

But how much of the lust to judge another fit for extermination derives from the need to distinguish venial sins from mortal ones, or hell, to just use the watered-down version: my powerless-person wrongs from the crimes of the powerful?

I’ve argued long here that fascism is a moral rot of the soul that says some people are better than others, and that no one, high or low, is entirely free of that poison. Edith Eger said we all have a Nazi within. When we cheer or just shrug at hoodie assassin, are we trying to turn a difference in degree (just one, direct and premeditated murder vs. tens of thousands of less direct, “collateral,” yet absolutely predictable and known murders) into a difference in kind so that we will be spared or praised, remain the “good people,” by calling attention to the really, really bad ones?

If you read A.R. Moxon at greater length (and boy, you think I’m lengthy), you’ll know that the theme of people believing themselves to be innocent and righteous as opposed to such awful, irredeemable others keeps popping up. The need to self-exonerate, to believe one’s shit don’t stink. To see ourselves as “the good people” as opposed to those folks out there, which gets fed and weaponized by bad actors 24/7.

Moxon tries hard not to essentialize: he’s pretty clear about what it takes to move from the “bad actor” to the “good actor” columns: face what you’ve done, quit acting badly, make reparations for your bad actions, do better. But the barrier is almost always the craven need to distinguish oneself as higher, better, more moral (cue Twain’s Hadleyburg) than others. And being a smol little bean of a powerless person unable to, say, deny 30-plus percent of health insurance claims in order to reap the acclaim and reward of one’s industry, peers, and stockholders, is one convenient way to make that distinction.

I think my desire to draw a line between the powerful and the powerless stems in part from this. It’s one of the reasons I don’t try to seek power.

When you’re a politics-head, the people around you sometimes urge you to run for office. This invariably makes me shudder. I may follow politics and think about it nigh 24/7, but I pretty much hate it. I hate what it does to people, especially the temptations it brings. Thank everything that’s holy I’d be terrible at politics, and my station in life is prohibitive for political success, not to mention all the nuclearly disqualifying things I’ve posted on the socials over the years. Because the weight of the temptations that come with politics exponentially grows, and let’s face it, the integrity and ethical fortitude of the people who do politics (and other kinds of power) does not keep pace. These days, it seems to run full speed the other way.

It’s often said that the people who should be given some degree of power are those who least want it. Almost universally, that notion is dismissed as unworkable. I’m not so sure it is, though I don’t know how we might make it work. In the world we’ve built, it’s certainly a laughable proposition, where nominees for power have to stump and pitch themselves to voters and donors and groups, begging for support and trying to (humbly) articulate why they are most deserving. Yet somehow, the alternative is considered absurd.

I dislike and distrust power, and I don’t much care who wields it. When it’s needed, it should be placed, lightly, in the hands of people of competence and capability who are widely regarded as legitimate for the purpose in question, and then only temporarily. Every word in that last sentence is heavy with meaning and load-bearing, but they add up to something resembling multiracial, egalitarian, pluralistic, accountable democracy.

My distrust of power applies especially to myself, because I’m more aware of my own failings and weaknesses than anyone else can be.

As a lifelong clinical depressive, I’m aware that this political belief may thus be rooted in a distorted personal thought pattern,5 perhaps born of Adverse Childhood Experiences and errant brain chemicals or completely different shit we’ve yet to discover. The upshot is, more or less: I have a conscience, and I’m at least somewhat aware of how much I have fallen short and hurt other people, and I’ve done so using only the measly, two-bit power of a white, cis-straight, male, Kansas nobody who’s never going to make $100K in a year in this lifetime. Just imagine the carnage I might have caused if I’d been, like, successful.

We’ve got a lot of folks in my general demographic who take their lives either quickly or slowly. They’re called Deaths of Despair. I don’t know how many of these folks presented with clinical depression before, say, middle age or layoffs or other such shocks, but some of the analysis of the problem concerns how these folks (and many are men) feel superfluous or betrayed or as if their lives have been wasted. They were sold a bill of goods about how the world would work, and now they are just anonymous, forgotten, poor, or declining.

Because I’ve been wrestling with this stuff all my days, I’ve no great feeling of sudden, crushing betrayal or somebody changing the terms of an agreement to which I was entitled. I tend to think the vast majority of all human beings through history have lived small, anonymous lives without great impact or notoriety. Why should I—or white American men in general—expect, much less believe myself entitled to, anything other than that? Patriarchy boggles me, even as I have to admit I soak in it.

But my disconnect also stems, I suppose, from a decades-long program to treat my depression by situating myself more healthily in my own mind. To self-convince that I’m not the worst human being to ever exist (such a grandiose villain delusion!), yet nowhere near some kind of exemplar or saint, uniquely deserving of a story-book ending. Life is just life, and shit happens. That’s going to be true even if we somehow succeed in making things fairer and more decent and humane for everyone.

So a big part of my coping is that damn quote I can never forget from The Catcher In the Rye, the one from (?) Wilhelm Stekel:

The mark of the immature man is that he wants to die nobly for a cause, while the mark of the mature man is that he wants to live humbly for one.

In some ways you can call the angel on my shoulder the mature man, and the devil the immature one.

The mature man still says, “Fuck the centrists,” but he doesn’t go out and shoot insurance CEOs. The immature little devil envies that hoodied gunman, even though the assassination won’t change the structure or its violence (calls for more private security are already up, which not only makes the next would-be assassin’s job harder, but ramps up the Us vs. Them dynamic between the elite power-holders and the rrest of us poor schmoes).

The immature man’s envy stems largely from the gunman’s willingness to say, “Fuck it,” and quit trying to live humbly for a cause, and that’s always the temptation. The immature man inside fantasizes about armies of hoodie-wearing revolutionaries like an American version of V for Vendetta; the mature man notes that Insurrection Act-happy Trump officials would cream over that possibility, and anyway, you probably won’t build a humanistic, dignitarian utopian atop the corpses of so many CEOs.

The people who made them corpses aren’t likely to have the disposition to build that world or live in it.

But I’m not horrified, and I don’t feel like a terrible person for not feeling horrified at Brian Thompson’s murder, because Brian Thompson wasn’t terribly horrified at the kind of life he led and how he made his money and acclaim.

I could always use more money, but compared to a lot of people in this world, hell, in my own town, I have a lot to be thankful for. In my own way, I’m privileged and lucky and spoiled. I’m a fairly unskilled menial worker, and yet even I have a limited scope of jobs I’m willing to do for ethical reasons (again, thanks to not being as desperate as I might end up being). I have to assume that Thompson was more credentialed, more skilled, more resume-accomplished than I am. He could have worked as a CEO of, say, a worthy non-profit in some medium sized city or large town in a hundred places in America, enjoying a comfortable and stable middle-class lifestyle and no major worries for the rest of his life—if he’d had any qualms about his job, if he didn’t prioritize the lifestyle he had, living where he did, enjoying the perks and access to upwardly-mobile elite-training- and playgrounds that he and his family likely did.

This doesn’t mean he chose to be murdered. It means he chose to do the work he did, and that work is ethically dirty, and he knew or chose “not to know” it was dirty. He weighed things and decided that dirty work was worth it.

Somebody else, maybe a thirst-trap named Luigi Mangione, weighed the same things as he saw them and decided it absolutely wasn’t. Then imposed that moral calculus on Thompson. Impactfully.

By contrast, I continue to resist imposing my moral calculus on people through the barrel of a gun. The debate continues to rage between the tiny avatars on my shoulders. The arguments each raises have their appeal, but there’s always a counter. audre lorde and A.R. Moxon are sounding off, but various revolutionaries and sometimes even sweet old Bing Bengtson weigh in, though I don’t know what exactly to make of Bing’s wisdom: it seems self-contradictory in a way: was the human person called Brian Thompson so beneath contempt that it was not worth the effort to kill him? That seems, in some ways, like ultimate horseshoe theory—so morally pacifist it becomes morally supremacist. Or maybe it’s just a bourgeois, cowardly cop-out. Bender from The Breakfast Club telling Andrew why he won’t fight him:

‘Cause I'd kill you. It's real simple, I'd kill you and your fucking parents would sue me and it'd be a big mess and I don't care enough about you to bother.

I can’t claim pacifism. I’m no Gandhi or MLK, though even MLK kept guns at home to defend against the Klan. As the Indigo Girls sing, “My friend Tanner she says you know me and Jesus we're of the same heart / The only thing that keeps us distant is that I keep fuckin up.” I will never go hunting Supreme Court justices, but I can’t say with much confidence that if Sam Alito appeared on my porch, I wouldn’t be overcome and uncontrollably launch myself at his throat the moment I opened the door and recognized that piece of shit. I really don’t get how that guy who ran into Tucker Carlson in a general store managed to contain himself.

So: manslaughter instead of premeditated assassination. It’s not much progress, but I’ll call it maturity.

Milan Kundera memorably wrote about vertigo, the desire to fall low:

…vertigo is something other than the fear of falling. It is the voice of emptiness below us which tempts and lures us, it is the desire to fall, against which, terrified, we defend ourselves.

Given Mangione’s privileged background, I’m suddenly thinking of “slumming.” Maybe something like Kundera’s vertigo is the urge behind “slumming,” although that always contains the cosplayer’s knowledge that one can return from the slum to the palace or penthouse afterwards, the dilettante’s dabble that makes the desire both doable and fraudulent because of its impermanence.

Depressives know the true desire to fall low as a descent more Virgilian:

It is easy to go down into Hell; night and day, the gates of dark Death stand wide; but to climb back again, to retrace one's steps to the upper air— there's the rub, the task.

John Darnielle explored the concept as he imagined a wrestler who always played the hero, but who finally had enough in “Heel Turn 2”: “Drift down into the new, dark light / Without any reservations / You found my breaking point / Congratulations / Spent too much of my life now trying to play fair / Throw my better self overboard / Shoot at him when he comes up for air.”

The vertigo for depressives is, of course, suicide. Sometimes, it’s even worse: family annihilation, or a long, slow road to self-destruction that drags others behind the depressive, like people dragged behind vehicles or horses as a form of torture or execution. The struggle is sometimes between a desire to do oneself the harm believed so amply deserved while sparing loved ones any pain as a consequence, which is, of course, impossible, creating a vice-like trap. Sometimes the pain becomes unendurable.

So you—or at least I—try to teach yourself that the script inside your head that endlessly condemns you is in error, that mistakes and failings aren’t damnations. That it’s grandiose and arrogant to imagine that the people who love you are all wrong or suckers you’ve conned with your superhumanly deceptive masking of your ineradicable worthlessness: maybe, just maybe, your brain chemicals or looping doom-mantras are the liars, and you’re no better or worse than the next person.

All the same, that struggle leaves a trail in the brain and the biography, and the idea of just giving up is always there, tempting, from some dark corner.

If you’re like me, a big part of the survival strategy is to take the privileges you do have and try to leverage them for others. It’s unseemly to advocate for yourself, because of the long history of self-loathing, and maybe you’ve managed to acquiesce to the overtures of others enough to allow people to love you to one degree or another. Those connections and that outward focus give you something to fight for, and fighting on behalf of others is okay, as long as you don’t hold yourself out as someone overly special in that fight.

Bonus! You can even pour far too much of yourself into that fight than health, or wellness, or sense, or “self-care” would advise, because such things stem from a place of self-esteem, and you hardly have any. You exist because of others, because you’re making a willed choice to accept it when they say they want you around despite all you believe about yourself, so fine, you’ll exist for them. That easily translates into self-sacrificial living, and damn the long-term consequences. Burning out is fine, says your legal-loophole brain; it’s not the same as directly causing your own demise. If I have to remain here, at least I can be here for others, be the tank and take the hits, and if it shortens my span, well, that’s kind of a secret upside, innit?

Yes, that is—absolutely—a damaged worldview, or at least the self-care revolution is trying to teach us, but it’s at least a stage on the road away from worthlessness. Maybe it’s as far as some people ever get, and if so, it has a smidge of honest, sad nobility to it, I submit.

What I want to suggest is twofold, however: that such an outlook is very, very close to direct action in the world akin or adjacent to that of our hoodied gunman; and that social conditions—and knowledge of how completely structures are rigged against folks just trying to live and get by—can replicate this mindset among people for whom chronic, clinical depression may not be an issue.

This perspective says, I may not be worth a damn, but others are, so I’ll go out in a blaze of retributive violence against the people who do such widespread harm with no accountability, with such insulation from accountability.

It says, I may not matter—they’ve made that abundantly clear—so my life is worth nothing if I sacrifice it to take one of theirs and puncture their bubble of impunity and security and deliver one small dose of consequences to people who otherwise will never, ever, face any.

Initially, it looks like hoodied gunman planned things with an eye toward escape and impunity. He seemed to have intended to get away with it.6 That suggests a level of self-worth and self-preservation a bit alien to me: were I to crack up enough to do what he did, I doubt I’d have much mental or creative energy to plan my retreat and fugitive post-game moves. I’d be too wrecked by the conclusion I’d finally given into to care all that much. In a very deep, ethical, and identitarian sense, I would have completely given up, embraced the vertigo, accepted the lowest fall, the complete heel turn. There would be no serious consideration of life after the crime, no fantasies about becoming a folk hero in the wind, of inspiring anything. The fundamental question that has plagued my life would not be answered; I would have finally given in to the fatigue of asking it, and given up all struggles. I would know I had no answer; I would declare myself inadequate to the question. I wouldn’t be able to sustain the tensions any longer.

And the image of myself of struggling to sustain the tensions is what, I think, makes me resist. It’s what enables me to not shoot people.

My job in this life is to serve as a platform for the angel and the devil to fight it out, even when they get boring AF, repetitive, cliche, outrageous in their radicalism, treacly and twee, when they keep running down dead-ends they’ve led me to more times than I can count. The record of their debates spool out of an old dot-matrix printer and pile up, getting heavier and heavier, but it’s my job to carry that weight—not because I think that somehow, an answer will eventually emerge, like the answer to Life, the Universe and Everything from Douglas Adams—but because I doubt there is one, because I suspect it’s the job of humans to carry such things and struggle with them and endure. I don’t know why that is. I doubt there’s any why.

I don’t believe I’ll ever be able to resolve the questions of justice or my own cosmic value. It’s not about that anymore. It’s more about endurance and integrity, which is funny because I’m a postmodern hodge-podge of slapped-together flotsam found in thrift shops, old books and movies and song lyrics, and left on curbsides for the trash guys: what integration is possible with those materials?

The good news is that I long ago jettisoned the idea that grand narratives were all that real. Some grandish narratives can be useful, for some purposes, of illuminating certain things, but always be ready to switch up as necessary. I find grand narrators to be too enamored of power, and as I said, I’m leery of power. I’m not a good candidate to wield it, and no one is for very long over much terrain.

So why don’t I just shoot people? Well, because I haven’t yet broken enough to make my heel turn. I haven’t yet given in to the desire to fall as low as I might. I haven’t yet cracked under the weight and the strain.

But I damn well know that temptation, that yearning. I live with it every day. It may not be what motivated the hoodied gunman, whether or not his name is Luigi Mangione. His youth alone made me doubt he was coming from the same place as me, though, as I said, enough caring about the world, about others, coupled with enough awareness of how structures are designed to perpetrate violence and supremacy, can, I think, replicate something like where I personally come from.

If people look at the world—or inside their own skulls—and see reflected there just disdain and indifference, just the cost of doing business and no sign whatsoever that all of us are “unique and irreplaceable works of art carrying intrinsic and unsurpassable worth,” then deaths of despair is what we will get, be they suicides or assassinations.

Is whacking a CEO right? I can’t go that far. The debate around my ears still rages.

But I can say it’s eminently natural. In Moxon’s terms, when structural violence has stifled value-creating and -nurturing natural human systems for so long, it’s not at all strange to see people conclude that it’s fitting when the natural systems finally respond as one would expect.

Even if it was this Mangione fellow, and if the weird mix of his influences and interests paints a strange story of his radicalization that fits into no neat categories, the takeaway might be that Brian Thompson’s death is a result of some bizarre tumors sprouted from the metastasizing systems we’ve built, but again, that’s fitting: dump who-knows-what into the water supply, and you’ll get wildly unpredictable behaviors in the populace.

Today’s subhead comes from The Mountain Goats song “Hostages,” off their concept album Bleed Out. Written by John Darnielle, if memory serves, during the pandemic lockdowns when he was bingeing old action movies like Rambo and Walking Tall and Deathwish, the album is a send-up of those films’ tropes and themes, though of course, in a time when half the world can’t see The Boys as antifascist, maybe some listeners will hear it as a celebration of 80s macho warfighting despite the lyrics. Anyway, “Hostages” has always struck me as the most ominous, creepiest song on the album, for its neoliberal, managerial, abstracted language, images of boardrooms and broadcasts. I think of Fox News and places like…corporate HQs for insurance companies. A hostage is a captive-audience member you threaten with death or harm. How that death or harm may come really isn’t the issue; it’s your number of hostages. That dictates your profits, your clout, your influence, your agenda-setting power.

The most relevant Mountain Goats album to this moment, of course, would probably be Jenny from Thebes, a rock opera or musical that tells the tale of Jenny, who offers her rented house as a crash pad for the down-and-out, until the town has enough of her philosophy that “this world is sad and broken / gotta fix a crack or two” and evicts her. She ends up killing the mayor, dumping his body in a water tower and hitting the road as a fugitive on her glorious Kawasaki.

John Wick going after the guys who kill his puppy is a major bit of this kind of porn for me.

“We live in capitalism, its power seems inescapable — but then, so did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art. Very often in our art, the art of words.” —the late, great Ursula K. Le Guin, acceptance speech for The National Book Foundation Medal

for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, Nov. 19, 2014.

The Indigo Girls themselves, Amy Ray and Emily Saliers, are kind of little angel-devil voices themselves, with Amy’s the rough, more punk and obscure, darker voice, literally and literarily, and Emily’s the voice of more sweetness and light. Unfair and simplified, but not entirely off-base, just look at the musical built on their discography, Glitter and Doom.

I was ookie about writing this whole thing, and then a couple of lines from Sam Adler-Bell hit me: “In a functioning democracy, politics isn’t separate from living.” This from what Sam speaks of as more columns from him, “situated at the intersection of politics and our psychic life.” Yeah, Sam is Freud-pilled out the wazoo, and yeah, I’m old enough to remember the inward turn of the 70s that seemed to derail the momentum of the counterculture and all that, but he isn’t wrong, either.

Getting “caught” in McDonalds under the reported circumstances, in possession of incriminating evidence, belies all this, but assuming our shooter was Mr. Mangione, it’s looking like the story won’t be neat and tidy any way one looks at it.