I try to leave my house as seldom as possible. I’ve long been this way. Nearly a decade working night shifts at a factory made it worse: what all’s even open for a day sleeper? When a second-shift job made things slightly more doable outside the home, COVID hit, and my irony was to be “essential,” so there was no working from home for half a year. Afterward, it wasn’t so much the virus as the social insanity of political polarization over, lord, germ theory, that made me want to avoid people for pretty much ever.

But when my wife—an avid runner—wanted to do a half marathon at the Crazy Horse Memorial in South Dakota, I offered to be her chauffeur. So I loaded up my migraine and depression pills, painkillers, knee braces and cane, as if to rebut my partner’s satchel of Goo, runner’s asthma inhaler, and confounding Spandex contraptions, and we did a round trip to the Mt. Rushmore/Crazy Horse area. Drive time was like 20 hours all told.

I don’t enjoy traveling the way most folks seem to. I think most people travel to see the sights, get souvenirs, take selfies, have “fun.” My wife and I did have our kind of fun, which is a long-married negotiation between her personality and mine, often consisting of me keeping certain thoughts to myself and trying to just be open to something for a moment without the darker downsides instantly crashing in.

It’s hard. I try to know about the world, at least the domestic United States, at least its politics and social conflicts. I have a cultural literate’s grasp of that stuff in history, so everything gets seen through two lenses. There’s the immediate sensory input of what’s out there, beautiful, quaint, sad, charming, funny, majestic, what have you. Then there are the ghosts of what I know about the places, the things, the totems I’m seeing. The ghosts always lurk.

Some people can see a pickup truck, for example, and just let their gaze roll off the vehicle. I tend to classify it as either a working truck or a show truck and remember that statistics show most pickup owners don’t use the damn things for, well, pickup truck purposes more than a handful of times each year. This, of course, changes the more you travel into rural areas and rougher territory, but every jacked-up, mega-wheeled, polished-or-wrapped monstrosity I see makes me think “lifestyle” instead of “working farmer,” and knowing the ballpark sticker prices of some of those giants doesn’t make me envious. It makes me speechless at some folks’ priorities and vanity. I start thinking about conspicuous consumption, vice signalling, status anxiety, and a bunch of dead sociologists until I shake it off and look for some wildlife as a palate cleanser. Wildlife good; people, not so much.

If you grow up Kansan, I believe it is your patrimony, your sacred inheritance and charge, to stave off the self-consciousness you feel about your home state by making fun of and mercilessly dragging the surrounding states. The insults are dumb and desperate, which is kinda the point, as self-derogating humor has been stapled to our identity ever since that Baum guy’s book got made into a movie. So Missouri and Oklahoma and Nebraska get it in the shorts. Colorado? They have legal weed and mountains, so we had to drop even the pretense that we were cooler. We just plain lost that one.

So here’s me reading my northern neighbor for filth: Nebraska is endless. I say this as a Kansan, so believe it. It’s got to be the winding roads, as opposed to Kansas’s eminently sensible straight ones. Please do not speak to me of Nebraska’s hills vs. Kansas being scientifically flatter than a pancake.1 You just can’t zone or Zen out in Nebraska the way you can in Kansas, which is the proper, meditative way to travel, because in Nebraska, there’s another damn curve ahead, probably with a hill to boot. Some may blame topography; I say the Cornhuskers were just lazy roadbuilders.

It’s been a long time since I drove through “where the West begins.” And it does begin there. I could feel Trump country rising around me—to be fair, just as I can in Western Kansas, although at home, it’s less intimidating, though more ardently proclaimed. Away from Kansas, I felt more imperiled. At home, I can still cite my Kansasness. Americanness is no longer enough, in case you haven’t noticed. At home, saying I’m from Salina—and this will absolutely slay some of you—a town of 47,000 on a good day, signifies that I’m…borderline, maybe not wholly lost to the Woke Mob, but I might bear watching, and I can usually finesse the uncertainty enough to get by. But outside my state, in regions where MAGA looks to reign unchallenged, people like me really are the enemy. I can’t even claim not to be, a mere victim of stereotype or collective judgment. I really do war against the “ideology” underlying what’s swept through a lot of this country, so I can’t maintain my innocence or noncombatant status. My warfighting objective may be a better world even for these folks, but I drive with a somewhat guilty conscience, like an infiltrator or spy.

The Nebraska Trump signage was far less prominent than back home, except in the gift shops at our destination. But part of that is the fact we live in town, where the divide is 2-to-1 GOP, not along low-traffic roads, a ranch house every parsec or two from the next.

I saw at least one contributing reason why MAGA appeals here. Every section of center pivot irrigation we passed—each say, 775 feet long, with 3.5-foot tall wheels at each support—just reminded me of the region’s dependence on corn production, the dwindling Ogallala aquifer, and the history of agriculture shifting to commodity production to the detriment of small farmers, small towns, and the sense of community and fellowship that all goes with it. When what used to be a small town of small growers and the small merchants and businesses that supported them becomes massive operations of distant competitors getting big or getting out, all thanks to the pressures of consolidated corporate behemoths and global trade, well, those incline one toward pretty diametrically opposed worldviews. Yet nostalgia for the former helps fuel the vengeance-and-grievance politics of those surviving in and subscribing to the latter. Make it make sense.

I should mention the finger-wave: you may know what I’m talking about. Hand atop the steering wheel, raise the index finger as you pass a vehicle on a two-lane road. You do it because…well, you just do it. As a child, I thought my dad did it because he literally knew and recognized from afar every single driver we were passing, and I was amazed at his social connectedness. Over time, the ritual has become more fuzzy but no less important.

I believe in certain archaic rituals, like clapping for every high school graduate who crosses the stage to get a diploma no matter how large the class is…and the finger-wave. At my present age and degree of understanding, I think the finger-wave is simply the nod of greeting one gives and returns as you pass a stranger walking down the street (which, I have learned from the Internet, is a freakish practice in big cities), just in your car or truck. It’s just what you do to acknowledge another human who happens to be on the same lonely road as you.

Very few finger-waves were returned on my trip. Compared to, say, Old 40 in Kansas. I don’t know what that means. Maybe it’s a sign that “the West” has begun.

Even rarer than finger waves were people of color on this trip. We were high into into Nebraska, say, Rushville, before I saw folks I’d peg as Native American. Such IDs are imprecise, but I’m trying to recall a single non-white-coded person I saw prior to that and coming up with nothing. I happily waved to the maids working at our hotel (janitor solidarity, you dig?) and heard them all animatedly speaking Spanish. Native folks on the Pine Ridge Reservation, of course, and at Crazy Horse Memorial, and at my wife’s run (I think the winner was a native guy, and one runner ran in fully regalia, which was absolutely baller). There was a Japanese couple with their adorable child on a Crazy Horse tour, but did I see even one Black person? Maybe in a passing vehicle at 65 mph. I’d like to think they would have stood out like a neon sign and I would have noticed. So I’m inclined to say I didn’t, and I’m inclined to think that the fact they would have stood out like a neon sign is why I never saw a Black person.

Days later now, I just got home from buying cat food, lest Chunky Cat suddenly waste away, of course. Salina’s not a multiracial utopia by any stretch of the imagination (we’re like 86 percent white), but despite the dominant whiteness of the customers at Dillons, even my short dash for that bag of Purina took me past a positive Rainbow Coalition of humanity by contrast to our trip. Our local Land Institute preaches the dangers of agricultural monocultures: how their lack of micro-ecosystemic diversity leaves them prey to all sorts of hazards from disease and climatic disaster.

Ah, but now we’re back to the massive crops of corn and their center pivots, the decimation of rural populations, MAGA isolation and epistemic bubbles. People come in all sorts. If you’re not seeing that, your ecosystem isn’t healthy.

Nebraska was just a penance to get to South Dakota, and it brought to mind how the state came to be, which brought to mind more of our current problems in the country, more of the MAGA problem, more of the “West beginning.”

Let me explain, borrowing from a Bill Moyers interview with historian Heather Cox Richardson:

…think about the Civil War as a war between two different ideologies, two different concepts of what America is supposed to be, is it supposed to be a place where a few wealthy men direct the labor and the lives of the people below them, the women and people of color below them, the way the Confederacy argued? Is that America? Or is America what Lincoln and his ilk in the Republican Party in the North defined the democracy as during the Civil War? Is it a place where all men are equal before the law and should have equal access to resources?

This is our context. Was our context back in Lincoln’s Day and before, and frankly, still is, as the title of the book Cox Richardson is discussing—her How The South Won The Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America (2020)—explains. It’s a battle of worldviews about America, about democracy, about what kind of democracy we seek and desire: an “illiberal democracy” of Christian Nationalism and patriarchy and rule by the rich, or a pluralistic, egalitarian, multiracial democracy where we all secure our rights and dignity and needs without having to suck up to those in power. It’s what we’ll be choosing between in a few short weeks.

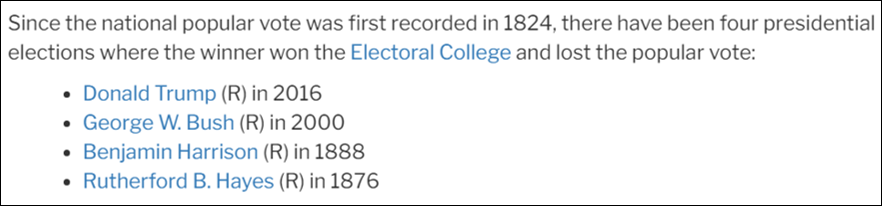

Reconstruction was that brief period when America seemed to be pursuing the right worldview. But our 19th President, the “staunch abolitionist” Rutherford B. Hayes, lost the popular vote and neither he nor his opponent had enough Electoral College votes to secure victory. Hayes made it into the White House in 1877 thanks to a famous “Compromise,” as Michael Harriot describes in his magnificent Black AF History: The Un-Whitewashed Story of America (2023):

…fifteen white men—five U.S. senators, five representatives, and five Supreme Court justices—gathered in a Washington, D. C., room and decided to give the disputed electoral votes to Rutherford B. Hayes, the Republican candidate supported by Black voters, essentially making him the president. In exchange, the whites-only room also agree to a plan that included three notable provisions:

REMOVAL OF TROOPS FROM THE CONFEDERATE STATES: In many places in the South, especially Louisiana and South Carolina, the military presence was the only thing protecting Black freedmen from white supremacist violence.

FUNDS TO INDUSTRIALIZE THE SOUTH AND RESTORE ITS ECONOMY: While this never really happened, it was clearly a nod to the white supremacists who couldn’t compete with the Black laborers.

THE RIGHT TO HANDLE BLACK PEOPLE AS THEY WISHED: The federal government agreed to essentially disregard the Constitution’s equal protection clause.

The ‘right to handle Black people as they wish” became known as Jim Crow. Across the country—not just in the South—states passed segregation laws and disenfranchised Black people en masse. The Compromise of 1877 was the definition of white supremacy: Black voters had given Hayes the presidency, and in exchange, he and his white co-conspirators chose white supremacy over equality.

Republican Hayes threw Black people under the bus, as Harriot notes, before there even were buses. While the GOP began with Lincoln and was the party that ended slavery, while the Democrats would rule the Solid Jim Crow South from 1880 for nearly a century, the post-Civil War Republican Party’s commitment to the ideals, the worldview, of equality turned out to be…ahem…quite malleable.

What else happened in 1877 besides the traitorous Compromise that brought Hayes into the White House?

An Oglala Lakota war leader called Crazy Horse was fatally stabbed with a bayonet by a military guard in northwestern Nebraska. The story’s details are disputed several ways to Sunday, owing primarily (it seems to me) to a clash of worldviews between the indigenous peoples and the frightened, hierarchic military and political establishment the Lakota had to deal with.

What the Army came to do was take away the Lakota’s guns—something that millions of my fellow citizens apparently fear will happen to them every single day in 2024—and then have them either help hunt and fight other Indians who continued to resist, or at least give up their entire way of life and religion. They say that dystopian fiction is when you take things that happen in real life to marginalized populations and apply them to people with privilege. They say that privileged people fear equality because if marginalized folks ever get equality, they’ll treat us they way we treated them.

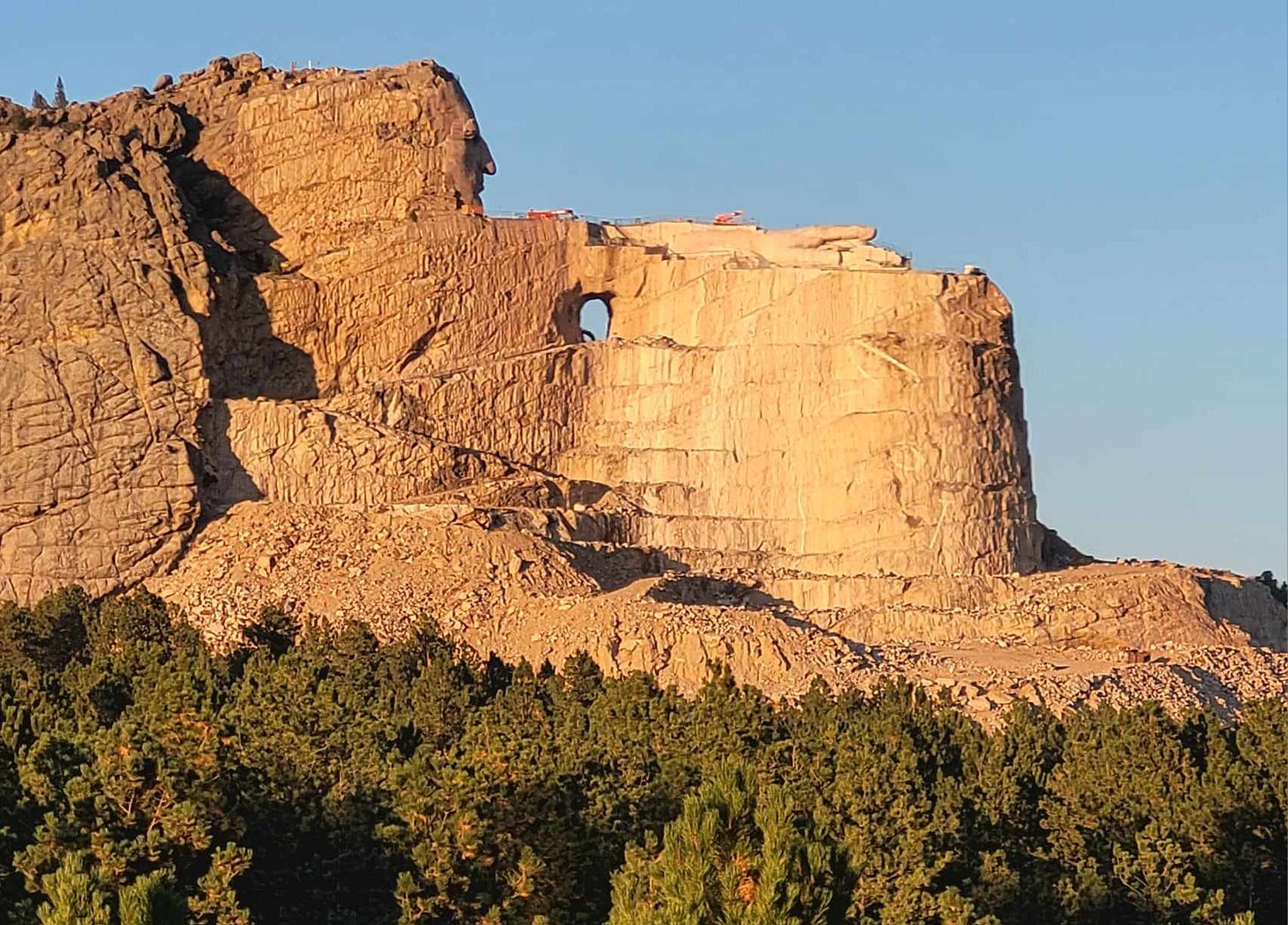

Whatever the case, 71 years after Crazy Horse’s murder, a guy would start carving up a mountain in South Dakota to resemble the Lakota warrior. 76 years after that, my wife would run a half marathon under the granite gaze of Crazy Horse.

Here’s Heather Cox Richardson on the West:

After the Civil War, Easterners moved West across the Mississippi in really large numbers after 1865….And in that West, they discover a land that is already susceptible to the idea of racial and gendered hierarchies, because it has its own history of them. And it’s a place out there where the new American system happens to be a really fertile ground for the Confederate ideology to rise again. And that’s exactly what happens with the extractive industries in the West that encouraged the heavily capitalized cattle markets, for example, or mining industries, or later oil, or even agribusiness. You have in the West a development of an economy and, later on, a society that looks very much like the pre-Civil War South. And over the course of the late 19th century, that becomes part of the American mythology, with the idea that you have the cowboy in the West who really stands against what Southerners and Northern Democrats believe is happening in Eastern society, that a newly active government is using its powers to protect African Americans and this is a redistribution of wealth from taxpayers to populations that are simply looking for a government handout. That’s language that rises in 1871, and that is still obviously important in our political discourse.

The “redistribution of wealth” in the form of taxes for public goods available to and benefiting everyone regardless of color, creed, or sex is a warmed-over argument from slavery defenders, as Richardson has often noted. Taking from the wealthy plantation patriarchs (who rose unfairly through the plunder and subjugation of the voiceless and enchained) or their gentry descendants to pay for roads and schools that everyone could use for the economic, social, and personal benefit of all—why, that’s “socialism”! The same claims are trotted out today, and I cannot believe I live in this cursed, looping, loopy timeline.

The rugged individualist who eschews and sneers at whatever the government offers, is also the proto-typical patriarch in the American mythos, the cowboy of the West, per Richardson:

…in the West, you get the rise of the image of the American cowboy…who is beginning to dominate American popular culture by 1866. And that cowboy — a single man, because women are in the cowboy image only as wives and mothers, or as women above the saloons in their striped stockings serving liquor and other things — is a male image of single white men. Although, again, historically a third of cowboys were people of color. It’s a single white man working hard on their own, who don’t want anything from the government. Again, historically inaccurate. The government puts more energy into the American plains than it does any other region of the country.

Historical accuracy? This is America, where in the year of our lord 2024, we are treated to the statement, “The rules were that you guys weren’t going to fact check.”

By 1888, Republican Benjamin Harrison is President, thanks again to the Electoral College and not the popular vote.

In hopes of long-term dominance in the White House, the Republicans admit six new states in 12 months. Richardson:

That was the largest acquisition of new states in American history since the original 13 and it’s never been matched again. They let in North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, Washington, and then Idaho and Wyoming to go ahead and make sure that they would continue to control the Senate, and the Electoral College. And they’re not hiding this. They actually go onto their media which is their equivalent of the Fox News channel at the time and say, by letting in these states, we’re going to hold onto the Senate for all time and we’re going to make sure we hold onto the White House for all time. But what that does is it begins to shift the idea of that human freedom. All of a sudden, the Republican Party, which has tried to continue to argue that it is standing in favor of equality, although that’s negotiable. After 1888 and the admission of those new states, the Republican Party’s got to start adopting that racially charged language in order to get the West on board. And that begins the change in American history that leads to a later union between the West and the South around this idea that really white men ought to be in charge. It’s not just a Southern thing. It’s a Western thing as well. And they make up a voting bloc in Congress that manages to change a lot of the legislation of the 20th century.

South Dakota was “born” as part of a blatant, naked, out-in-the-open, partisan effort to “pack the union,” I guess you could call it, by admitting new states that would vote Republican.

Today, we have equality- and justice-based calls to admit Puerto Rico and Washington, DC, as states for the purposes of actually representing the 3.89 million people who live there (more than the populations of Wyoming, Montana, North and South Dakota combined). These calls are going precisely nowhere, and even the Democrats won’t play hardball to fight for either right or their own party’s, or worldview’s, advantage. Then again, the worldview is really that of the left wing of the Democratic coalition, who vote Dem for lack of any better option and get blamed for frightening “centrists” into reactionary camps whenever they speak most honestly about the world that should be made.

Back in 1888, with new states in hand, the Republicans had to ensure their partisan loyalty. So they increasingly pandered to hierarchies of human beings, with the transplanted Civil War worldview of supremacy asking for its tribute, spurning and scorning government investments they were, in fact, getting. Some people are worthy, some worthless. Some are “real Americans,” others less so or “foreigners.”

History certainly does rhyme if not repeat.

When I was a kid in school, we probably made Thanksgiving Indian headdresses from construction paper and learned all the sanitized, cherrypicked, and whole-cloth made-up stuff about pilgrim and settler interactions with the Native populations. Over the years, I’ve learned a bit better and a bit otherwise about those stories. So it was important for us to make sure we at least traveled through the Pine Ridge Reservation en route to our destination.

You know how you can tell when one county or state ends and another begins, by the state of the roads? You can absolutely tell you’ve crossed into the Pine Ridge Rez the second you do so. It looks poor and neglected. That’s coming from a white guy from central Kansas who works as a janitor, so there’s tons of cultural assumptions I’m trucking in. I don’t know what all I don’t know here, but I dare anybody remotely adjacent to, let alone above my social station to disagree.

I don’t comment much on Palestine and Israel here, not because I don’t have deep, wounded feelings and opinions on that region and its peoples, but because I feel entirely out of my depth even trying. The history is a weight, and it’s a weight that keeps me so far underwater that I feel like I have to master it, know its contours and details, so I can unchain myself from it to surface, draw breath, and utter even a single sentence about the present day. To speak about it is to erect a DEBATE ME sign beckoning every counterargument based in bad faith and partial understanding. Add to that the hasbara, the spin or propaganda or apologetics from Israel and vehement Zionists, and the respect I try to maintain for communities and cultures that are not mine. Add to that the unreliability of so many sources of information nowadays, including venerated newspapers who are demonstrating untrustworthiness in coverage across a number of fronts (cough—trans people…cough—Israel and Palestine…cough—sanewashing of Trump).

It is not at all unfair, unjust, or a stretch to draw comparisons from Pine Ridge to Palestine because a similar weight crushes down. The temptation to pontificate here is stronger, because Pine Ridge and the other reservations are ours in a way that, complicities aside, Israel and Palestine just aren’t quite. Over there, we’re at least one step removed. We can’t claim any such distance here. We just can’t.

Driving through the reservation, I could instantly visualize the original sin of capitalism—enclosure—right there in front of me. The Rez may be vast—so vast, really—but it’s still enclosed, if only by laws and rules. Add to it the money economy dictating every aspect of life and foreclosing every alternative, and you get a people who used to move freely and sustain themselves now sequestered in place without access to the jobs and resources the world has decreed are requisite for having a decent life. They may still be on the land, but how long can you survive this way? How long can that relationship sustain you when material deprivations continue to pile up?

We white people like to talk about tests of faith, but we know nothing. I can’t claim an iota of understanding of what the land means to native peoples, and I can’t claim that they are a monolith in subscribing to that meaning to the same degree, but I would bet the meaning the land holds for them is infinitely deeper and more essential to their cultural identity than what we hear from family farmers no longer able to practice the trade their grandfathers or great-grandfathers pioneered in these parts. This is not to siphon away sympathy or empathy from those farmers. It is to note where our sympathy and empathy already flows, and the tales of heritage and meaning that register and resonate with us, compared to those that just…don’t. I suspect we view the family farm tales as stories of time and labor invested by families in one place, primarily to subsist, then inch ahead, then maybe thrive and grow and expand into leisure and comfort and grandiosity—the American Dream of up-ratcheting generational prosperity through hard work and sacrifice. No wonder our sympathy goes to them. It’s our worldview. By no means does it lack dignity, but it never had a monopoly on it, either. Until we enclosed and deprived the folks who lived and breathed and subscribed to a different worldview, the folks who’d been here before us.

Now many indigenous people have to be perversely semi-grateful that Donald Trump put Neil Gorsuch on the Supreme Court. Because it turns out Gorsuch has made Indian law kind of his personal hobby, so he’s not quite as awful there as one would expect, given his record on almost everything else. But the randomness of one guy’s hobbies shouldn’t be what holds out thin and occasional hope for down-and-out people.

The town of Pine Ridge sits maybe 12 miles as the crow flies from Wounded Knee, site of the infamous massacre that gave Dee Brown his 1970 book’s title,2 as well as Buffy St. Marie the title for her song. We didn’t visit Wounded Knee. I couldn’t justify doing so except as a hasty tourist, and that wasn’t how I wanted to go if I ever do.

But the 1890 Wounded Knee Massacre, pace Heather Cox Richardson again, isn’t divorced from presidential politics, or from the seemingly endless battle between at-odds Americas. It starts with tariffs:

Before the Civil War, Congress levied limited U.S. tariffs to fund the federal government, a system southerners liked because it kept prices low, but northerners disliked because established industries in foreign countries could deliver manufactured goods more cheaply than fledgling U.S. industries could produce them, thus hampering industrial development.

So, when the Republican Party organized in the North in the 1850s, it called for a tariff wall that would protect U.S. manufacturing. And as soon as Republicans took control of the government, they put tariffs on everything, including agricultural products, to develop American industry.

The system worked. The United States emerged from the Civil War with a booming economy.

But after the war, that same tariff wall served big business by protecting it from the competition of cheaper foreign products. That protection permitted manufacturers to collude to keep prices high. Businessmen developed first informal organizations called “pools” in which members carved up markets and set prices, and then “trusts” that eliminated competition and fixed consumer prices at artificially high levels. By the 1880s, tariffs had come to represent almost half a product’s value.

Buoyed by protection, trusts controlled most of the nation’s industries, including sugar, meat, salt, gas, copper, transportation, steel, and the jute that made up both the burlap sacks workers used to harvest cotton and the twine that tied ripe wheat sheaves. Workers, farmers, and entrepreneurs hated the trusts that controlled their lives, but Republicans in Congress worked with the trusts to keep tariffs high. So, in 1884, voters elected Democrat Grover Cleveland, who promised to lower tariffs.

Republicans panicked. They insisted that the nation’s economic system depended on tariffs and that anyone trying to lower them was trying to destroy the nation. They flooded the country with pamphlets defending high tariffs. Cleveland won the popular vote in 1888, but Republican Benjamin Harrison won the electoral votes to become president.

After the election, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie explained that the huge fortunes of the new industrialists were good for society. The wealthy were stewards of the nation’s money, he wrote in what became known as The Gospel of Wealth, gathering it together so it could be used for the common good. Indeed, Carnegie wrote, modern American industrialism was the highest form of civilization.

But low wages, dangerous conditions, and seasonal factory closings and lock-outs meant that injury, hunger, and homelessness haunted urban wage workers. Soaring shipping costs meant that farmers spent the price of two bushels of corn to get one bushel to market. Monopolies meant that entrepreneurs couldn’t survive. And high tariffs meant that the little money that did go into their pockets didn’t go far. By 1888 the U.S. Treasury ran an annual surplus of almost $120 million thanks to tariffs, seeming to prove that their point was to enable wealthy men to control the economy.

“Wall Street owns the country,” western organizer Mary Elizabeth Lease told farmers in summer 1890. “It is no longer a government of the people, by the people, and for the people, but a government of Wall Street, by Wall Street, and for Wall Street.” As the midterm elections of 1890 approached, nervous congressional Republicans, led by Ohio’s William McKinley, promised to lower tariff rates.

Instead, the tariff “revision” raised them, especially on household items—the rate for horseshoe nails jumped from 47% to 76%—sending the price of industrial stocks rocketing upward. And yet McKinley insisted that high tariff walls were “indispensable to the safety, purity, and permanence of the Republic.”

Basically, the Party of Lincoln used tariffs to leverage industrialism to beat the South: good for them. But that lucre was addictive to the titans of industry, and since tariffs are ultimately paid for by consumers in the end, keeping out pesky business competitors to boot, the titans could maintain their position at the top of the human hierarchy by squeezing the common folk for every penny. After all, the titans were the best and most deserving people. If they weren’t, how come they were so rich?

But class divisions in America always tend to give way to racial fears of the scary Other, and politicians have known this since the institution of slavery. Most poor whites didn’t own human chattel: if they supported a system that benefited only the rich planters, it was because they were sold a worldview that told them their whiteness meant that, no matter how poor they might be, at least they weren’t Black, thus placing them in solidarity with the rich folks who wouldn’t piss on them if they happened to be on fire. Since the Civil War’s worldview of human hierarchies of worth and value had spread into the American West, targeting the “savages” to ramp up support for the Republicans and distract from the common person’s sufferings under plutocratic tariffs had to be a no-brainer.

Richardson again:

…with the admission of these new states in 1889 and 1890, the Republicans believe that they are going to do very well in the midterm election of 1890. And the big thing on the table in America in 1890 is the tariff – high walls around the American economy that protect businesses inside America, they protect them to the degree that because they face no foreign competition, different groups can collude with each other to raise prices. So in 1860, the Republicans insist that an economic downturn that’s been happening is only because those tariffs aren’t high enough. What happens in the election of 1890 is the Republicans think they’re going to win and they lose dramatically. It turns out when these ballots are counted, a Republican Senate or a Democratic Senate hangs on the seat of South Dakota, on one Senate seat. And that Senate seat has pretty clearly been corrupted. There’s a huge fight, then, in the legislature of who actually won. So there the situation sits.

BILL MOYERS: Sits there, for sure, with President Benjamin Harris needing to shore up his support in the Dakotas. So, he sends corrupt cronies out to replace experienced Indian agents and dispatches one-third of the federal Army as well.

HEATHER COX RICHARDSON: And with that movement of the Army into South Dakota in the largest mobilization of the US Army since the Civil War, Lakota are trying to negotiate with the Army that increasingly wants to bring them into the reservation, to the agencies to make sure that they’re under control. And over the course of the next few months, that situation escalates until a Lakota leader, Sitting Bull, is killed in December of 1890. And then in terror after that, a group of Miniconjou Lakota move across the state. They actually find the Army, the Army doesn’t find them. And in the process of corralling them and disarming them later on that month, the soldiers start to fire. And about 250 Lakota are massacred. So, it was a massacre that was really directly attributable to whether or not the Republican Party could control the US Senate in order to protect its tariffs that promoted big business, and protected a few oligarchs.

Here’s Donald Trump in late September of this year, resurrecting a tariff regime to fix our factually strong economy:

You know, our country in the 1890s was probably…the wealthiest it ever was because it was a system of tariffs and we had a president, you know McKinley, right?... He was really a very good businessman, and he took in billions of dollars at the time, which today it’s always trillions but then it was billions and probably hundreds of millions, but we were a very wealthy country and we’re gonna be doing that now….

Need I mention the Haitians in Ohio? The “bad genes”?

If you’re going to the Crazy Horse Memorial, you’re practically a stone’s throw away from Mt. Rushmore.

We drove by the famous, almost required carving, snapped a pic or two. I’d seen it as a kid. Over the years, I’d learned the backstories not taught to me as a child. Accordingly, we didn’t give any money to Mt. Rushmore. The fact that the road there is named after sculptor Gutzon Borglum, pal of the Klan,3 just enrages. I was probably in my late 40s before I ever registered the term Six Grandfathers, which is shameful. If you’ve ever read Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (1970)4 and come away ready to take up arms against the US government (past, or hell, maybe present), or learned of the Treaty of Fort Laramie, I don’t see how you can look at Mt. Rushmore without at least shaking your head.

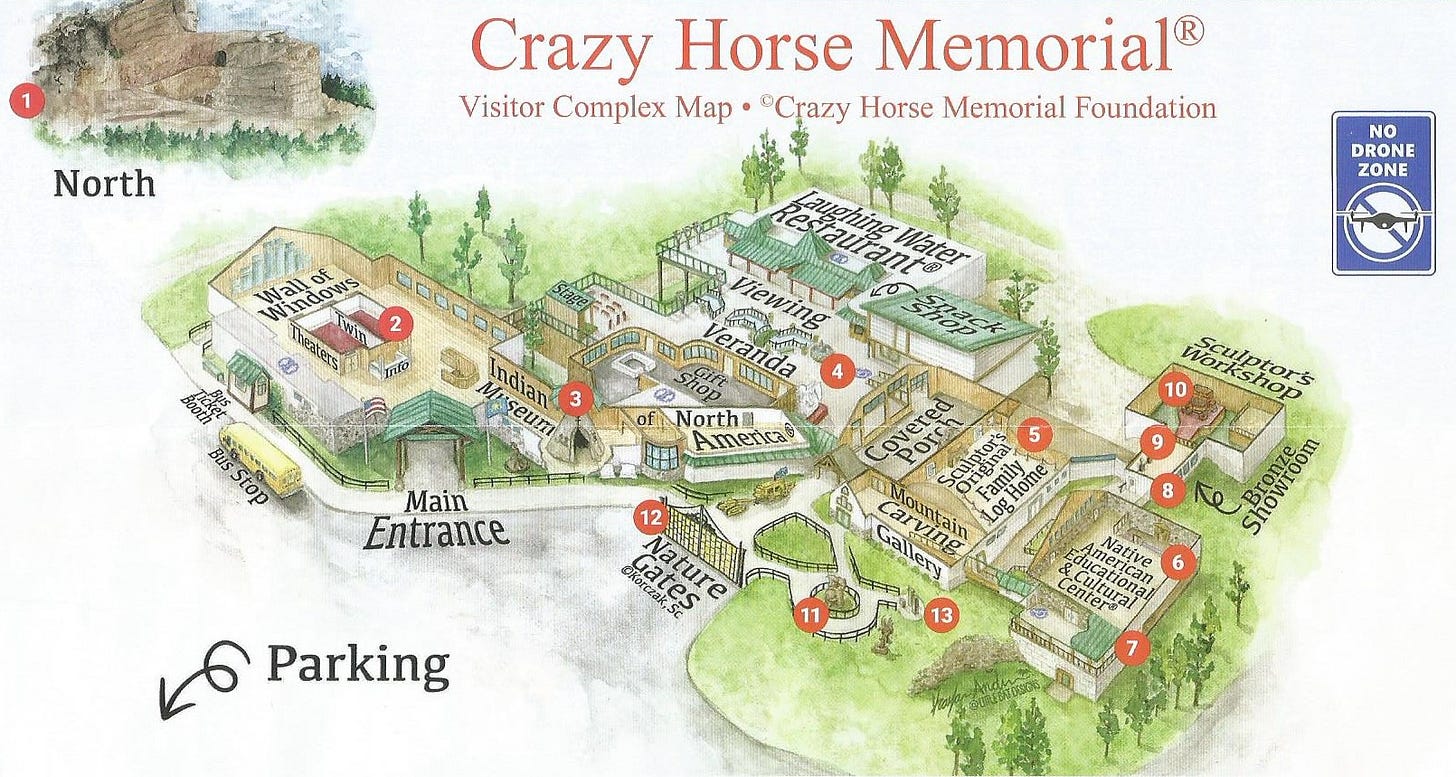

We did spend money at the Crazy Horse Memorial. Its history and meaning are…a more mixed in my mind. The sculptor, Korczak Ziolkowski, though he worked under Borglum for a while on Rushmore, doesn’t seem like the kind of guy who’s currently and rightly burning in hell. Per the promotional film at the site, Ziolkowski seems to have been a basically decent fellow, his vibe very Grizzly Adams, sincerely moved by the historic injustices done to the Indians. Crazy Horse is immense. It dwarfs the Presidential heads of Rushmore. Per our tour guide, you can fit the Rushmore heads in the space between Crazy Horse’s cheek and the end of his windblown hair. A school bus can fit on Crazy Horse’s finger, with room to walk around it. It certainly won’t be completed in my lifetime, and the work continues under the surviving descendants of Ziolkowski.

The whole story, however, leaves me ambivalent. The idea for the monument came from Henry Standing Bear (no, not the Lou Diamond Phillips character on Longmire5), an Oglala Lakota statesman who recruited Ziolkowski for the project. Standing Bear was educated in white schools and may have come to a somewhat “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em” view as regards big, carved mountains. Standing Bear’s older brother had lobbied for Gutzon Borglum to put Crazy Horse on Mt. Rushmore, to no avail. Maybe this sort of thinking was perfectly understandable back in the 1930s, but the idea of copying what the whites did to Rushmore, only with Crazy Horse as the subject, rubs me wrong, and I’m not entirely alone in this. Per Wikipedia’s entry on the Memorial:

Other traditional Lakota oppose the memorial. In his 1972 autobiography, John Fire Lame Deer, a Lakota medicine man, said: "The whole idea of making a beautiful wild mountain into a statue of him is a pollution of the landscape. It is against the spirit of Crazy Horse."[29] In a 2001 interview, Lakota activist Russell Means said: "Imagine going to the holy land in Israel, whether you're a Christian or a Jew or a Muslim, and start carving up the mountain of Zion. It's an insult to our entire being."[30]

In her 2019 New Yorker article, ‘Who Speaks for Crazy Horse?’, author Brooke Jarvis states, “On Pine Ridge and in Rapid City, I heard a number of Lakota say that the memorial has become a tribute not to Crazy Horse but to Ziolkowski and his family”

This last point hits. The Memorial’s focus, frankly, is on Ziolkowski and his family. Yes, there are native crafts, art, artifacts, and memorabilia everywhere. You can’t throw a genuine piece of pegmatite granite from the work up the mountain without hitting something connected to indigenous history or culture. But the center of the story is Ziolkowski and his vision and project. Around that narrative is a cloud of other stories: his hardscrabble labors under pioneer conditions, raising the family, the grand vision of the sculpture and the many decades it would take, the reasons for commemorating Crazy Horse (which serve as the entry for the Native culture and stories). The overall tale is that of the man, his vision and project, and the happy fact that the subject of that project is a Lakota warrior is what allows Indian lore and heritage in the door. The native culture forms part of the cloud of stories surrounding Ziolkowski and his descendants, but it is they who sit at the center.

Which raises the question of alternate history. What if Henry Standing Bear had given up the whole idea? What if Standing Bear hadn’t approached Ziolkowski? What if Ziolkowski had blown Standing Bear off as Borglum did? (What if Standing Bear had sought some kind of consensus among the other Lakota elders instead of going what seems like pretty solo with this whole notion?) Would knowledge of native culture and history be better off or worse if the Crazy Horse mountain was “just” a mountain today, with no visitor center, museum, school for native university kids, etc., etc.?

Was Standing Bear’s whole approach tainted with a kind of hubris, commissioning a century-long (or more) project, grounded in a kind of whiteness, born of his accomodation to assimilationism? I own a t-shirt (from Red Rebel Armour) that reads THINK 7 GEN AHEAD. It’s meant to be a reference to the notion6 from the Iroquois Constitution advising leaders to deliberate carefully about the impact of decisions they make down through the future, even to the seventh generation that follows them. While it’s pretty certain that a ginormous Crazy Horse statue carved from a granite mountain will last that long and longer, the thinking behind it, the perspective on native life and livelihood that animated Henry Standing Bear—has that endured?

It seems to me it may have not lasted even 30 years—to the American Indian Movement in the 1960s, let alone the Land Back7 movement of today, the efforts to educate white settler colonialism about the errors of its ways, while its chickens—the newest ones named Helene and Milton—come home to roost. It feels almost as if Henry Standing Bear carried some sense of defeatism, a desire to memorialize what was vanishing from the earth, as assimilation claimed more and more of his people, perhaps himself included. The mountain carving thus takes on a shade of a burial marker, a Great Pyramid for the aliens, or just the irreparably alienated, to find one day.

Or maybe Standing Bear was right, as cynical or sad as it may be: does it take something as grand, imposing, and generations-in-the-making, yes, one that participates in the myth of the rugged white individual fighting the elements and refusing the government’s “help,” leaning only on his kin and neighbors, to get other white folks to pay attention and thus, trickle down a little concern, tangentially, for the people Standing Bear believed in helping?

I can’t know or say. I can’t tell you if people who go to the memorial leave with an appreciation of history or culture that’s in any way authentic or grounded. I can’t tell if I inched toward that goal myself for my short time there. Are the items in the museum gift shop crafted by indigenous artists? By indigenous artists on the Rez? Or folks who’ve gotten out and now make their livings in thriving towns that can support galleries? What’s the museum’s cut, which is to say, what’s the cut for the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation? The students who attend, tuition-free, the college run by the Foundation on the grounds, what’s their education like? Are they training to assimilate into wealth and power and dominance? Are they learning to use the master’s tools, whether to disassemble the master’s house or just to survive in the world the master made and imposed? I can’t tell you if there’s an opportunity cost involved in the money people spend at the Memorial versus what they might spend at Pine Ridge or elsewhere on the Rez. Or any other Rez. Would folks even drive through the Pine Ridge Reservation if not to get to places like the Crazy Horse Memorial and, yes, Mt. Rushmore? Do people come away from the Memorial thinking of the grit and legacy and awesome vision of One Man while viewing the blurred-together cultures of the various native peoples as just a melange of things now irrevocably gone and fallen and never to be seen again? Too bad, so sad. At least they’re remembered here.

As if they’re not living and breathing in patched trailer houses around towns like Pine Ridge, the storied place where Henry Standing Bear spoke with passionate anger in his eyes about the Treaty of Fort Laramie to Korczak Ziolkowski. You’d think there’d be a tie-in to their well-preserved meeting place in Pine Ridge, akin to The McLean House at Appomattox where Lee surrendered to Grant. But as far as I know, there isn’t. At least it wasn’t mentioned in the Memorial’s film.

It made me remember my college days, reading about Jean Beaudrillard and his notions about hyperreality, which is a whole, weird Sargasso Sea of French philosophizing, but might be summarized as “references with no referents.” It’s a lot, and I can’t claim to be really down on it, but at the time I got a little plain-spoken purchase on it by way of reflecting on the difference—as I saw it—between art and hyperreality.

It seemed to me that art should refer us back to life, perhaps not literally, as in a piece of art that tries to depict a subject photo-realistically, but in the sense that experiencing art should make us leave the encounter wishing to re-engage with life more fully, more attentively, more truly in some way. Art should sharpen our eyes and other senses, make us feel more alive to things, more open to the world around us. I’m sure this experience is different for each person, but that’s my non-artist gist for the feeling.

Something that’s hyperreal is more “real” than reality, so to speak. It’s a complete experience while at the same time, a complete fraud. It refers us back to… nothing. When it’s complete, when it’s over, it’s gone, finished. It is so…more, so much, so bigger, so intense, so hyper, that it simply breaks with the real world and has nothing to compare itself to. It’s of another order, but not in the sense of conjuring an awe we can participate in later, in snippets and small moments, when a piece of the experience is reflected back at us from our normal lives—as when a line or scene or image from a novel or poem recurs to us in an odd moment, say—but something completely Other, manufactured, alien. Art refers us back to our lives in a richer, deeper way, empowering our senses and sensibilities to experience more powerfully what the artist condensed or distilled in the work; hyperreality breaks us utterly from our lives and leaves us unable to return with any psychic souvenirs, only the dross merch we bought at extortionate prices from the vendors at the show, bits of cheap, branded plastic that will gather dust and fail to conjure anything but a wistful reminder that our lives are paltry in comparison to the other-worldy experience of that hyperreal encounter manufactured and simulated for our brain chemistry right then, not our soul forevermore. Art is humane and humanizing, connective, generative; the hyperreal is something entirely inhuman, ultimately alienative, neuter.

Maybe I got Beaudrillard completely wrong back in the day. I don’t care. I like my version just fine. Following my take on it, the Crazy Horse Memorial is a long way from a modern-day pop idol concert extravaganza. It’s hardly the Metaverse or whatever Zuckerberg dreams of that weird shit becoming. It’s of a kind with, if not on the scale of, Disneyland, which, if I recall, was one of Beaudrillard’s exemplars of hyperreality.

But I have to wonder to what extent the experience of Crazy Horse refocuses people back toward the people he came from, who are still alive and nearby, though safely far enough away so as not to harsh the curated image of the facility and the questions raised (or at least able to be raised) by its narrative. The sculpture itself is said to aim to depict the “spirit” of Crazy Horse, and I don’t know if I understand what that’s supposed to convey. I don’t know if I’m capable of understanding that. I also don’t know if anyone can, if we’re not referred back to actual life surrounding the monument, which includes the Rez, the controversies, the questions, what was then and what is now.

Which raises the question: this great work of Korczak Ziolkowski and his descendants, is it art? If the work itself qualifies, does the tourist institution built up to celebrate it, propagandize it, market and fundraise for it, undermine its artistry as it tries to gild its lily?

No, the lily was the mountain, before the first dynamite blast.

What’s grown up around Ziolkowski’s work in progress is more like a gilded frame, etched with every reference that reflects well on the man whose work is slowly unfolding on the mountain. It draws the eye.

How much it draws the eye, from what, toward what, I’m not sure.

Fine, fine. Stephen Vincent Benet coined the phrase. But the mood was too understated.

Seriously, read the whole entry. Stone Mountain is an abomination. The US Mint issued commemorative coins to help fund this obscenity. Borglum may have pitched some kind of hissy and broken with the project, but there’s zero indication he did so over the Klan’s views.

I keep referencing this book. It’s not necessarily an endorsement, more an artifact of my own past. It was influential. I cannot speak to its historical accuracy in all things. But emotionally, it will make you want to time-travel back and join the Lakota, if they would have you.

I’ve not read the Craig Johnson books, though I’m curious after watching the TV series. I wouldn’t be surprised if Phillips’ character were an intentional reference, homage, or update to the real Henry Standing Bear. It semi-sorta fits. Sheriff Walt Longmire’s fictional Absaroka County is, after all, a tribute to a movement to pull parts of Wyoming, South Dakota, and Montana into a new US state that would have included both of the big mountain sculptures.

7th Gen is also a slogan of some of the university programs run by the Crazy Horse Memorial Foundation. And do note my weasel words here: “meant to be a reference to a notion.” It’s because, well, I think certain ideas have general purchase within cultures whether or not you can cite a written source that’s authenticated, and the whole topic of the Iroquois Constitution is sorta already a square peg crammed into a round whole of western white concepts, I suspect, and was, as far as I can tell, more an oral tradition kind of thing anyway. What I care about here is that it’s a watchword, that it’s got serious roots in indigenous cultures, and it’s relevant to my point. Plus, we sure as hell should have long been heeding it. Why couldn’t us settlers have stolen the worldview of the Indians instead of, well, everything else they had?

Forty-four years ago, the Supreme Court ruled that the Treaty of Fort Laramie that promised the Lakota Sioux “ownership” of the Black Hills had been breached by the federal government. The court declared the feds owed the Lakota money for that theft, with interest now over a billion dollars. The Sioux, as far as I know, have left that money sitting on the table to this day because it’s about the land and their relationship to it.