I read the news today, oh, boy.

And yesterday, and the day before that.

Looking forward, there will 1460 days in the next Trump Administration, and that’s assuming it lasts only four years.

That’s assuming he lives through his term. That assumes he leaves office if defeated in 2028. That assumes free and fair elections in 2028. That doesn’t even get into whether or not voters will have a remotely accurate picture of his track record or its meaning by then in the face of everything that tells us the disinformation and misinformation will only ratchet upward between now and then.

We know this dance. We did it before. It was, um, crazymaking? Every day a new outrage.

Recently I was introduced to this apparently classic John Mulaney bit:

This time around, I doubt we’ll find much funny or funny-able. There’ll be more than one horse this time. They’ll own and staff the hospital. Some will be dragged from the trunk of RFK Jr.’s car. They’ll be skeletal hell-beasts ridden by Pestilence, War, Famine, and Death. Probably some less infamous equestrians in the regiment as well.

Anyway, it’s going to be a lot worse trying to cope with current events this time around.

Two options immediately present themselves:

Zone out: unplug, stop paying attention. If it’s important, you’ll hear about it. Problem here is that this feels irresponsible, and it may be literally dangerous. You run the risk of missing an opportunity to act to protect or prepare or protest (literally or vocally), when that’s the right and necessary thing to do.1 You also run the risk of depending on a grapevine of hearsay to inform you, and that’s one of the reasons we have another Trump Administration.

Dive in: immerse yourself in it all, follow all the feeds. Insert every filmic plot point where the character is in danger of losing his or her identity / consciousness to the swirl of the hive mind / Borg / stronger will / overwhelming mind-blowing vastness of the cosmos / whatever, lest they have the anchor of the love-interest’s hand in theirs or a little spinny top in Inception.

Journalist Marisa Kabas triggered a big discussion on Bluesky by just throwing out this comment:

There has to be a better way than sounding an alarm every single time a deranged, Trump-related story drops. It’s unhealthy and unsustainable. We need to find a way to stay informed without spiking cortisol and without losing sight of the bigger picture. I’m just…not sure how.

And Roxane Gay was another great mind thinking the same thought:

In the next couple of months I need to figure out how to stay informed without endlessly exposing myself to all the dark (probably accurate) predictions of how Terrible Trump Part Deux will be. It’s just too much, seeing all these doomsday scenarios.

Once upon a time—or so my always trustworthy nostalgia tells me—the news media itself kinda served this function, but it did so with the cooperation of scads of norms and institutions that formed a kind of safety harness holding a presidency in the driver’s seat. A POTUS could not leap from that seat, set the stands full of race fans on fire, do naked cartwheels, release ravenous leopards on the pit crews, then hop back in the car and careen into dozens of other vehicles, forcing them into the wall.

There once were countervailing branches of government, departments that served the people and not just the president, a professional civil service, lawyers and advocates, etc. Presidents worried about legacy and reelection and the chances for others in their party. We maybe(?) don’t have these anymore, or they maybe don’t much matter(?). Who the hell knows?

So Kabas’s and Gay’s problem is everybody’s problem.

“Managing” this “Chaos”

First, get rid of half the dictionary definitions for “manage.” They do not apply. Why? Because they assume the workplace manager. One who oversees or supervises or controls.

We little people will be doing none of that. All the pop-business professional development training you’ve been doing since you first entered the workforce and had to sit through a breakout session’s Powerpoint?

Useless here.

Instead, look to the other half of the definitions, the ones that speak of surviving or withstanding. Managing on too little sleep. Managing to get by despite everything that’s going on. That’s what we’re aiming at: getting through this without falling into catatonia or blasting outward in an explosion of centrifugal force.

Second, ponder the history of “chaos.” Today we see it as meaning utter confusion and uncertainty. Once upon a forgotten time, we understood chaos as the Greeks did, as the vast abyss of Tartarus, the void.

Both are kinda true today. We will feel as if we are shouting into a void, staring into an abyss, because we’ll be facing a kind of uncertainty that will be hallucinatory and mind-breaking.

For most of us, most of the time, normal life will carry on: work, errands, home, work, errands, home, what-have-you. But within this microcosm of same-shit-different-day will be the ever-present knowledge that Evil Clowns are behind the wheel of the United States, there are no speed limits, no Highway Patrol, they’re drunk and high, heavily-armed and road-ragey, and converting the vehicle into a Mad Max Fury Road death machine while they’re driving it.

The messy, confusing, up-is-down, walls-are-melting uncertainty of “chaos” is the more modern meaning of the term, and what’s happening at present. There is really no predicting what this will look like. There are guesses all over. I tend to be skeptical of the downplayers, but that doesn’t mean I think we’ll have stormtroopers marching down my main street in late January 2025. That said, I read a pretty cogent and plausible post the other night outlining how World War III has effectively begun and will unfold, so there’s…that. The point is that anything can happen, and that’s plainly terrifying to both a lot of people who either have no experiences with chaos and people who have such experiences and a great deal of trauma from them.

Rather than suggest specific strategies just now for how to take in news and current events (which I may do later or in response to questions…I have some thoughts2), I’d rather focus on overall mindsets for how to approach a period of chaos and how to survive it.

It probably “helps” if you’ve ever survived life under an arbitrary, authoritarian figure like an abusive parent or partner who utterly controlled your life and wellbeing. Given that model, I think the spectre of “chaos” prompts certain main responses

The Managerial Response

I tend to assume the folks who opt for the Managerial Response have little experience with the kind of radical uncertainty we’re in for. Or maybe they were “broken” by the experience or dealt with it in a particularly unhelpful way.

The managerial need to remain in control of what and who they manage is the root fault, I think.3 What they imagine they can control can be an institution, large or small. It can also be an area of some expertise, and the older that expertise is, the more dated the period in which the expert exercised active command of facts and agency in their domain, the worse things seem to be.

I think we see both versions (institutional control and control of authoritative knowledge of how the world works) in the glacial pace at which institutional authorities have responded to the new reality of Trumpism in fields like law and journalism.

Merrick Garland and law professors did not meet the moment. The New York Times and Washington Post certainly dropped the ball. Shitposters and trolls and podcasters and YouTubers and billionaire accelerationists and incels and manosphere influencers and Kremlin inspired (or hired) “political technologists” turned out to be the forward-thinking folks. Those who placed their faith in norms and staid institutional values look like the stuffy toffs we associate with stick-up-the-ass British-coded academics from 1950s boys-school period dramas.

The irony is that masses of people turned out to shore up and defend the institutions that would serve as guard rails, and while it was enough to get Joe Biden into office, it wasn’t enough to prevent a return of Trump or a definitive discrediting of Trumpism. The truth, the facts, didn’t set people free. Such a crushing blow to the “liberal” or just Enlightenment identity. And such a myth to cling to for so long.

Look, institutions take time to develop. For this reason, just about any time you find an “institution,” you can think “legacy” or “established” or “kinda old-school.” Which just means grounded in a decent chunk of the assumptions taken for granted from the system of norms and rules and laws and structures we’ve had in place for quite a long time (varies depending on the institution in question). To rise to the head of an institution requires (usually) some degree of training, experience, expertise, proof of ability and fitness or at least indications of potential.4 Inseparable from all that, interwoven with that, is increasing socialization into the norms of the institution.

Sure, institutions undergo change. For instance, I recall when schools went through No Child Left Behind. That was a big deal5. But, whatever it may have augured, it didn’t fundamentally alter the entire terrain of public education in America or undermine the assumptions, rules, and laws upon which public education was based and built. We’re in a period now where literally anything goes, we don’t know what, and we may have very little power to affect any of it.

The Global Financial Crisis of 2007-2008 may have been the biggest whopper since the Great Depression, but we had normal governments in place that still played by and adhered to normal rules and regimes. Unfair, bail-out-the-rich rules in many cases, but you could kinda count on elites to try to preserve the economic system writ large and not allow, much less welcome, the collapse of the world’s economies. Not sure we can depend on that anymore. (In a year or ten, the dollar might be replaced with Dogecoin for all I know.)

We (at least some of us) literally lived through this with COVID. Who really anticipated that the head of the US government would seriously float the idea of individual states competing against each other in economic or fealty markets for medical supplies? Who had that on their “managing chaos” BINGO card? Who among us normies who all got our shots as kids6 grasped the extent of the anti-vax movement or the way it would morph into a partisan militia? And now we have RFK Jr. nominated as HHS Secretary: the upheaval to nearly a century of public health he could/would usher in is beyond the ken of the usual paradigms of “managing change.”

So anybody at the head of an institution—large or small—is by definition fairly socialized into a world where radical uncertainty, chaos, in their profession or field, is bracketed into really small-ball categories by comparison, and has never occurred on anything remotely like the scale we’re facing.

I don’t envy managers. They’re stuck in institutions built under the old rules, confined and constrained by those institutions. Even if a manager overcomes their socialization, no established institution with any clout in a community allows the head guy to charge into battle left and right. That dude is restricted to maintaining continuity, maintaining reputation, maintaining mission focus and credibility.

All of those things fare very badly in a world where real chaos is on the table. Or dissolving the table with acid.

Managers can’t rapidly innovate, pivot, or rise to meet dramatic moments when the public world does that thing from Inception or Doctor Strange where the cityscape wraps around itself and folds into an Escherian LSD trip. When the entire system spasms and reverses polarity. Especially when that polarity reversal is to something predating civil service reform, the economic lessons of the 20th century, the Warren Court, the end of Jim Crow, the 19th Amendment, all wrapped up in a delusional ball.

Part of the reason is that managers really aren’t independent. They’re nested within Russian dolls of greater or lesser institutional bureaucratic fiefdoms. Department heads have superiors. Checks have balances. Non-profits have funders and partners and PR to worry about, to say nothing about government grants and legal status.

I work under a military veteran who has made a personal and professional study of the social psychology of change dynamics and corporate culture in order to do his job more effectively. I think his service background helps him with this.

But even a military mindset has limits. Exceed mission parameters? You’re out or on a shit list at least. That constrains both him and his people.

Protect your people? Yes, but when the entire theater of conflict and chain of command above, below, and around you goes FUBAR (cough—Hegseth! cough—Gabbard! cough—Gaetz! cough—RFK Jr.!), that may simply mean hunkering down to the new, denuded “mission” and instructing your people to keep their heads down—not much help for avoiding Moral Injury or making a difference.

Ultimately, the usual analogous thinking tends to rely on air support from higher-ups or extraction to safety and resumption of “the mission” somewhere else at a later point, but if things break as bad as is possible under Trumpism, this will simply not be in the cards at an institutional level.

Many institutions, even if conceived of as “units” in a larger campaign, will simply not survive, so the notion of “at least I’m protecting my people” dwindles day by day until collapse of even that illusion.

There’s a famous graphic about circles of control, used, I guess, to help with anxiety. Here’s one:

In a world of radical chaos, this image becomes a curse. Control’s circle shrinks and shrinks7, as does the circle of Influence. One beef I have with managers and people in power is that they truncate their circles of Concern to those things they can either influence or control, which translates—eventually—to historical and contextual ignorance and lack of imagination about how they might actually be able to influence things they once cared about before they allowed their concerns to be whittled down to the demands of their profession.

It’s a kind of triage: Can’t do anything about it, so I’ll focus elsewhere. Which means the the creativity born of frustrated concern and yearning for justice or solutions dies, and one day, the “not my jurisdiction” impulse becomes automatic dismissal. Not only in their own minds, but projected outward at anyone who looks to them as the smart and capable heads of institutions and says, “Isn’t there anything you can do about this?” When asked, all they can see is a wall. That wall is composed of all the brain cells they allowed to die off through starved disuse that pile up atop one another when they pulled back their thinking to focus only on what was actionable within the other two circles.

I think this is a major reason why (1) a lot of institutions have failed us, and (2) the “Manager Response” to the kind of radical chaos we may well be in for is going to be singularly unhelpful and a disappointing location to park all one’s faith.

The Flashback Response

A flashback, in terms of subjective experience, places you right back in the moment where you were previously under threat. You’re back in the jungle or desert under fire. Or hiding in the closet or under the bed while the raging abuser trashes the house searching for you, gun or other weapon in hand.

It’s not just a metaphor. Trumpist rule threatens the arbitrary domination by people who often shift between smarmy smiles and violent threat. Structures one might have depended on previously—from rules and laws that kept such people in check through fear of consequences or their educational function (enforcing such rules and laws sends a strong message of cultural condemnation of the behavior)—are now, or soon will/may be, up in the air.

I think people fixate on the wrong part of the equation here. They zero in on the “domination” and blow past the “arbitrary” part. But for anyone who has undergone abuse, it’s the arbitrariness that’s truly terrifying, or so I believe.

There is no rhyme or reason. There is no predicting what will set the abuser off. There’s no control. No power to steer one’s own fate. No autonomy, no real choice. It’s all whim. It’s all about what action or inflection, what gesture or facial expression, what intonation or perfectly normal utterance that, yesterday, went unremarked or maybe even garnered a chuckle or praise, may today set the abuser off into a volcanic rage or a cold, sadistic program of dehumanization.

No matter how long one has lived under such an interpersonal regime, there is never any surety. What heretofore hidden neurons will fire in the abuser’s gray matter to turn the long-constructed “normalcy” upside-down and replace it with terror and pain?

This is why abuse survivors and others frequently develop hypervigilance, the constant, searching, quasi-paranoia about potential threats or subtle signs of things that might go or be wrong. From veterans who won’t sit with their backs to doorways or windows to “people pleasers” who seem to fawn and fret over the slightest twitch of a facial muscle during a conversation. It’s the desire to predict the unpredictable, to corral into manageable portions the essential arbitrariness that is the real danger—as they have been taught so painfully. The desire to take in all sensory input, to see and hear and sense everything, alert for any sign of danger or threat so as to head it off at the pass or at least be somewhat prepared for what will come if one can’t.

It may be needless to say this, but in a world of algorithmic endless scrolling, where the current events of the entire world are the “abuser,” the spectre of the arbitrary threat never, ever goes away. Life becomes, in a sense, an eternal state of scrutinizing the abuser for the moment they will turn.

And because abusers are sadists, even ostensibly reassuring news about how the abuser in power did something that “isn’t as bad as we feared” is only—at best—a momentary reprieve. There’s always another shoe to drop. There’s always the chance this was a feint, because abusers love to see us drop our guard and embrace the illusion of safety just before they remind us to fear and why we should fear and whom to fear.

It’s the arbitrariness. That’s what “lack of guardrails,” “no more adults in the room,” and all the rest really translates to for people who have firsthand experience with the kind of folks we just handed all the reins of American power to.

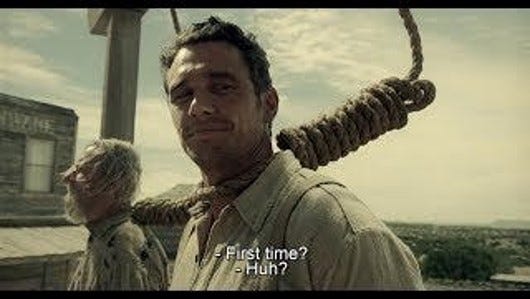

The “First Time?” Response

This one’s tricky. Maybe even dangerous. It straddles the line between cynicism and survival in a world of arbitrariness and chaos. All the same, I guess this is kinda where I live a lot of the time.

The lesson I took from my own experiences of arbitrary abuses of power that threatened and hurt me was that all the trappings of protection, order, normalcy, and decency we tend to rely on are, at the end of the day, very fragile, paper-thin, precious, and entirely built and maintained by human beings. They are not the Natural Order. They are not decreed by God or the Founding Fathers. They are not the ineluctable working out of the moral universe arcing toward justice.

These are nice things to imagine to be true, I guess, but I always see them as potentially lethal myths, because arbitrary abuse of power keeps happening, and when it happens to people who believe in an Order of Law and Right in the World that Protects and Shields Us (or Should), such people often shatter from the sharp, unexpected blow.

It can be the shock of learning that the police have absolutely no legal obligation to help you (Uvalde, but pretty much in general8 ).

It can be when you’re unfairly fired and you learn of the hoops you must jump through to get any kind of justice, and then that turns out to be, like, lost wages at best, while in the meantime of this long process, you’ve been evicted for lack of income to pay your rent, had your car repo’d, and so on.

It can be when your crummy landlord refuses to fix your apartment, but jacks the rent anyway, then manufactures BS to keep your security deposit, and you never thought to meticulously journal and photograph every inch of your living space for the past two years to fight such evil, and now you discover that the law is stacked in your landlord’s favor.

It can be when your kid gets racially or sexually hassled at school and the school does bupkis about it, citing all sorts of excuses, rules, and liabilities then talks to you like you’re a particularly slow character from the Andy Griffith Show.

So I tend to go through life enjoying the moments when structures, laws, and norms seem to be relatively stable and supported, when there are rules on paper, even though I know those are often figleaves as well, but always trying to remember that what really matters is who has the power, and what they can—if push comes to shove—do with it. Most people are decent enough most of the time, and most of the time, you can count on that. But crises and threats tend to make people look after themselves first, and that brings out sides of them that are ugly or that accept the ugly. (Just look at what those motivated by “inflation” voted for.) Lying, hypocrisy, fudging the narrative, manufacturing facts and justifications, throwing people under the bus—all these things can and do happen when folks face threats to their own safety, jobs, ambition, and so on, and the rules and policies in place are only as strong as the countervailing power to make folks abide by them.

I want to live in a world where we live by what we say. Where we aren’t raging hypocrites. Where we have integrity and don’t sacrifice the inconvenient people or principles when times get hard. That requires not just official rules, but the power to make people follow them9, and if all the power is above us in a hierarchy, well, by definition, we’re relying on a small pool of people to do the right thing on behalf of a lot of people who can’t really help or hurt them in return. Trust but verify. Tit for tat.

Rules don’t enforce themselves, and having a special class of rule-enforcers just opens the door for hierarchal imperatives, corruption, and capture among the rule-enforcers. Rights especially do not prevent abuse. At best, they might provide grounds for vindication, restoration, and reparation of some kind way far down a long and expensive road, but they do not serve as some kind of force field that magically deflects tear gas or batons from peaceful protestors no matter how scrupulously they are following the “rules” of exercising their First Amendment freedoms.

So the world I live in is always, sorta, fake. I go through it appreciating things when the illusion holds, when people abide by the illusion of a stable order, refraining from engaging in the Hobbesian war of all against all, but I’m always kinda taking the temperature on how that pro-social illusion is faring.

Accordingly, in anticipating Trump 2 World, there’s a part of me that looks at the radical uncertainty, the real arbitrariness of what’s coming, the anything-goes chaos that’s absolutely stitched through with abuse and sadism and revenge and cruelty, and says, “First time?”

I try not to say this to other survivors of traumatic abuse. It would be vicious and mean. But there is a tendency to want to say this to folks who’ve long believed that the institutions or the Robert Muellers or Jack Smiths or the courts or the latest Presidential nominees or Committee Chairs would save us. There’s really a lot of system- or hero-worship happening whenever somebody has a good viral clip of a celebrity non-Trumpist dressing down one of the bad guys. These are fun enough, but, jeez, really not accomplishing much. Especially when the systems have been so gamed, undermined, and infiltrated by bad-faith actors for so long.

Being semi-sorta philosophically used to this is not, I should stress, the same thing as being immune to all the feels that go along with backsliding and defeat. It’s very hard to prepare folks to deal with chaos in my way: until it crashes down and people have their dark nights of the soul, it seems wrong and cruel to try to disabuse them of the faiths and myths they put their trust in. Even when things go to hell, it seems like depriving people of flotsam to cling to as they try to stay afloat.

But preparing to live in a truly arbitrary, chaotic time means everything’s on the table. If you place your trust in X…let’s call it Y, shall we? “X” has now been thoroughly discredited, thank you Elon…you have to contemplate how Y can just be ignored, or bulldozed, or assassinated by Seal Team Six by order of a constitutionally immune President. These things are possible now because of the power dynamics and the Right’s victories. Whether or not such actions will have consequences later is up in the air. Whether such anticipated consequences will deter the behavior is anybody’s guess—that stuff goes to psychology and intent and nobody is sure what the hell goes through the minds of Trump or various factions of Trumpists at any given moment in time.

The upshot is that the “First Time?” response is to sort of recall the realization that nothing ever was all that stable, no matter how it seemed, no matter what kind of semi-secure bubble we might have carved out for ourselves in our various recoveries. To dust off those memories of extreme hypervigilance (to the extent they ever gathered any dust) to stay flexible for anything that might come down the pike, while trying not to become debilitated with paranoia and panic. To place hope and faith only contingently in persons in high places, in institutions: To stave off despair by saying, Well, there are still options, but to acknowledge that those options may very well come to nothing and develop or be willing and able to develop back-up plans.10

To remember, perhaps most of all and above all, that we as survivors learned valuable lessons from having gone through reality-upending, utterly at-will abuse in the past, so in many ways, we may be well-positioned to cope with this new world in ways that people who never suffered those horrors are not.

It’s not an enviable role to be cast in, but it doesn’t have to re-victimize us. We can sadly and resignedly view it as having been promoted to AA Sponsors of a sort: we’ve got more experience with this sort of thing, so maybe we aren’t such bad choices to hold the flashlight and someone’s hand as we tiptoe at the head of the line through the dark tunnel, be it a segment of an Underground Railroad or a sapper’s campaign of sabotage.

For years now, The West Wing has come in for derision for its depiction of a vision of left-liberal politics as fantasy-land wish-fulfillment. Which is true. If I can be accused of having watched porn, well, The West Wing qualifies. It would be great if the world worked the way Aaron Sorkin depicted it. But what stands in memory from the series are certain human moments, like this one, where Josh Lyman emerges from a therapy session and encounters his boss, the recovering drunk, Leo McGarry. The story, a revamp of the Good Samaritan, is apt for this moment.

Yeah, Leo’s a boss, a manager, and yeah, Leo’s own managerial blind-spot is evident: “As long as I’ve got a job, you’ve got a job.” (Protecting the people in his unit, assuming that the chaos can never grow so great that even the great Leo McGarry could fall from his powerful position, be thrown from it, be defenestrated, whacked by Seal Team Six, etc.).

But still, the human bond, the framing as friend in the story is what counts and resonates and gets you in the feels here, I think.

The doctor and the priest: consider them pundits who have axes to grind or priors to prove: insulated, important folks who either think they can control what’s going to happen (even if they have enough freedom or disposable income in their own lives to manage some kind of soft or safe landing for themselves), or are in denial about the scope and scale of what could conceivably happen—a hole opening up beneath them at any moment.

Us little folks can’t afford such denial. Sure, we’re tiny, but that just means we’re not priority targets. We can still be collateral damage. We or those we legitimately care for.

We’re in the hole, or we know those who will be, might be.

The strength of the “First Time?” Response is to be Joe, the guy who hops down alongside his friend and “knows” a way out.

No, we don’t know a way out of this hole. But we’ve been in analogous ones. We’ve been in other dark places with no help from the important people who believed in Systems and Rules and Order and Divine Plans.

We know that holes can just appear and people can fall into them, because the world is unstable, the universe doesn’t have constants or covenants, no matter what the scientists or theologians say.

And even if we fail to find a way out, we’re in there with our friend at the end.

On the other hand, there may be fewer occasions for rapid-response mass turnouts during Trump 2. These may well be suicidal if things go really bad. Nobody can say, and each case may be completely different.

Here are a few:

Get off Twitter.

Don’t get too enamored of the “I only want straightforward news, not analysis or interpretation” advice. It presumes that you know enough to meaningfully do the analysis and interpretation yourself, and no one knows enough subjects from enough angles to do this with everything, and everything will be subject to the avalanche. Do this with subjects you know well where you can trust your own analysis and interpretation. For other subjects, you’re still going to need meaning/impact whisperers to break it down for you. And it’s a good idea to have a diversity of perspectives there, too, so you don’t get sucked into a silo or echo chamber and calcify into a “it’s a troll!” or “it’s 9-dimensional chess!” or “we’re doooomed!” or “nah, it’ll be fine!” or any other school of “thought” that tends to attract desperate followers. Decent interpreters will make cases for why they think as they do, and they will be humble enough to concede no one can be sure. In the process, they’ll explain themselves and mentally walk you through what could happen, which at least sketches out the possible, so maybe if it happens it won’t entirely break your brain.

I won’t presume to advise the seriously targeted and marginalized, because I suspect they and their support networks know how to protect themselves far better than I could preach at them from my perch. They are smart at this, of necessity.

Those who love people who are seriously targeted and marginalized, however, have steep and varied learning curves to climb. This is not ideal. These folks are probably ill-equipped for the many scenarios and radically different strategies out there. Do you bravely admit you know and love marginalized people to help defend their existence and rights? What about when the Gestapo grabs you up and demands you name names? How do you parse that uncertainty? Are you capable of being a normie public voice for decency and right on the one hand all the way up until your relative privilege means exactly nothing and you have to grab a go-bag and leave your house and pets and trackable vehicle and phone and everything else you own and run? I’m not being all that hyperbolic here: these are the kinds of polar extremes chaos really forces you to plan for, or at least imagine, and I’m very, very sorry if I’m the first to tell you this. Ponder these things now in the zone of ethics and imagination, then try to pick your information consumption accordingly.

Nothing wrong with certain coping mechanisms and therapeutic interventions and insights, of course. Focusing on what’s in your control is wise general advice and not to be jettisoned in a period of radical chaos. But what we have always believed was under our control is precisely what can change in times like these, illustrating how adaptive techniques become maladaptive when the environment turns upside-down.

Well, it used to. We’ve become semi-inured to the right-wing practice of installing people at the top of institutions for the express purpose of hobbling or undermining or dismantling those very institutions. And since Betsy DeVos—nay, Sarah Palin?, nay, Dan Quayle?—we’ve been inured to rank fucking amateur incompetents thrown up for these jobs. Insert Caesar appointing a horse to the Senate here.

Reagan’s “A Nation At Risk” report was even bigger, in terms of laying the ground for privatization and vouchers, but that really dates me.

Even those of us who understand the inherent risks of trusting governments too much, and those of us familiar with the history of medical experimentation on populations deemed less-than or expendable?

We already live in a world where controlling one’s own physical body is not assured. This is reality for women in about half the states. If Comstock becomes enforced law again, make that all the states. Controlling one’s personal, intimate choices? See LGBTQIA+ folks. Controlling what one thinks and reads and says? See book bans, meddling in school curricula, dismantling the Department of Education’s anti-discrimination rules, destroying federal labor protections, “impoundment’s” ability to withhold funding from any entity disliked by POTUS, the recent bill to pull non-profit status from “terrorist” entities, so much more. We haven’t even entered into a world where paramilitaries need to roam around intimidating people to silence and conformity yet—these are all just straight-up legal maneuvers.

“Neither the Constitution, nor state law, impose a general duty upon police officers or other governmental officials to protect individual persons from harm — even when they know the harm will occur….Police can watch someone attack you, refuse to intervene and not violate the Constitution.” —Darren L. Hutchinson, professor and associate dean at the University of Florida School of Law.

The other half is to make the world less deadly: if a co-worker or boss or landlord’s functionary can do the right thing, get fired for it, and not end up living in a cardboard box for that integrity while they sue or search for another job, then this safety net improves the odds of people doing the right thing. Integrity and decency should not always be pitted against survival.

I hope, if my own learning curve permits, and if I can extricate myself from this unhappy role of civic armchair therapist, to start delving into some of these “backup plans” ere long.