Three Days in August

JVL tiptoes toward grasping what "conservatism" has always been

I subscribed to The Bulwark mainly to read Jonathan V. Last. I’ve shared his Triad column many times, and I appreciate his analysis on a wide variety of topics. I find him fairly nimble in his thinking almost all the time, especially for a “tempermental conservative,” as he has described himself. I think he fights a good fight: against MAGA and Trumpism, for moral decency, for sanity.

I wouldn’t call him a comrade. Despite his growing openness to radical maneuvers, I think in many ways he’d like to go back to a status quo that I’ve long believed was untenable and now pretty much think is ripe for yeeting into the sun. For instance, in a recent piece, he offered this bit:

More than anything else I have always been a temperamental conservative. I believe that the world is precarious and that what we have, right now, might be as good as it gets. So we ought to conserve it and make changes only slowly and deliberately.

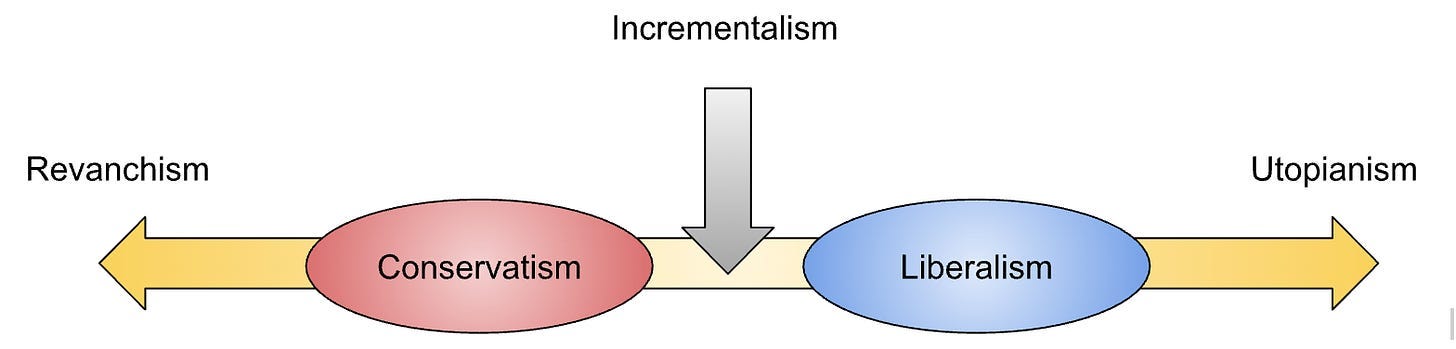

In the broadest possible sense, the danger of conservatism is revanchism and the danger of liberalism is utopianism—those are the radical edges of the spectrum where people believe that big changes can create good outcomes. And yet history shows that truly big changes mostly result in tragedy.

One way to view the ideological spectrum is like this:

That little gray area in the middle—that’s where I like to operate. The place where you make tiny course corrections, never going too far one way or the other.

But maybe that will turn out to be the wrong model for confronting authoritarianism? If it turns out Americans do reject authoritarianism and aren’t willing to ride this rocket into the ground, then maybe it will require operating outside my preferred incremental zone.

Or maybe not. That’s tomorrow’s problem—and one we’ll be lucky to have.

JVL’s been on my mind lately partly because I’ve shared so much of his content. Where I live, it seldom serves to pass along fully-automated-gay-space-communism analysis. Here, we are are just simple farmers, people of the land, the common clay of the new West, you know...morons.

Alright, terribly unfair to me and mine.

But a kinder way to say it is that folks can manage to get down JVL’s sometimes lost, lamented status quo content easier than they can swallow critiques of authoritarianism that kick off with prison abolition and defunding the police. And his arguments can serve as a mind-opener to those sorts of critiques if handled well.

But I’ve also been mindful of the time I frothingly disagreed with one of JVL’s pieces.

JVL Dissects A Frog

So I finally caved to the onslaught of incessant email teasers from The Bulwark and gave them $8 a month. Mainly so I could read Jonathan V. Last, whose The Triad submission “What Does ‘Conservatism’ Even Mean Anymore?’ just buried my curiosity needle too hard.

It was about his typology of “conservatism,” which is relevant here, and it just struck me as shockingly naive.

JVL is at least sympathetic with “conservatives.” At least a bunch of the old school variety, at least if they stayed grounded enough to realize that Trumpism is stripping the United States for parts and turning the country into an authoritarian graft-fest. So, he’s been on the right side for about the last ten years, minimum, more so since the founding of The Bulwark in 2018.

To do this, he’s had to accept and grapple with the heel turn of the Republican Party, and, to a lesser extent, of American “conservatism” more generally. To reject the GOP is somewhat easier for pundits and educated folks. After all, a political party is just a shell, a video game console. You can swap in or out any old game cartridge you want to play, and it will oblige. The Democrats used to be the party of slavery and Jim Crow, at least in the South. Lincoln was a Republican. Black voters supported Republicans until FDR. The phrase, “I didn’t leave the ____ party. The ___ party left me!” isn’t a new coinage. It’s at least as old as reactions to the New Deal, and you heard it from the Southern racists, libertarians who opposed income taxes, and other progenitors of the modern conservative fusion of the 1950s and their descendants as they struggled to decide if they would try forming a third party or take over a major party from within.

(Spoiler: They took over a major party from within.)

So it’s easier for some elite folks to part ways with a political party, despite the ways party affiliation can sink its claws into your identity over time. Just fall back on the technical truth that parties are containers whose ideological contents can be emptied out and replaced with different fluids, or poisoned by some contaminant, and there’s your out.

What’s harder is rejecting the contents that a party allegedly used to contain—the ideology and proclaimed principles—so unceremoniously poured upon the ground by the usurpers who took over. Such is the fate of “conservatism” in the minds of folks like (I suspect) Jonathan V. Last and many ex-GOP Never Trumpers, even to this day. We even saw echoes of it in Biden’s paeans to bipartisanship, how he took pains to speak only of MAGA Republicans, not simply Republicans, despite the manifest wholesale capture of that party by nihilized arsonists.

Basically, it boils down to: There was and is something valid and valuable about “conservatism,” and we need it in politics. More, only one party can provide it, the GOP, so we must be conciliatory and never alienate them in toto.

For JVL, I suspect the baby sloshed out with conservatism’s bathwater is mainly dispositional: a hesitancy and skepticism about “utopia.” Suspicion of grand, brazen, untried and untested, pie-in-the-sky initiatives that often seem indifferent to the massive complexities of systems already in place and how freakin’ entrenched and justified and thorny these are to futz with while avoiding catastrophic unintended consequences. This disposition and argument serves him well when tackling, say, the DOGE debacles, as well as his recurring Leopards Eating Faces posts wherein Trump supporters voted to “punish the baddies,” only to find that they’ve enabled a would-be dictator to strip them of benefits, kill the industries that keeps their towns alive, and deport their beloved neighbors of 30 years. Ignorance has consequences.

But is it really “conservatism” that avoids this trope of utopia? Utopia is coded as foolish idealism, a yearning for no-place, a province of the young, while conservatism is the attribute of the old and wise. The odds certainly favor elders having seen more varieties of bullshit and scams in their time, recalling more instances of efforts to fix and improve things that fell short or backfired, so watch-words like “Be careful,” “Study what came before,” “It’s complicated,” and so on, will probably always be valuable. We presume elders have learned more about complex systems for having navigated and worked in them and presumably tried to reform or alter them, perhaps in their own idealistic youth.

But is this so? Or is it simply a cultural trope? Is it an old saw from generational lore, especially dominant since the Boomer sixties? I’m not trying to claim that the association between elders and wisdom, or youth and foolishness, is bunk, merely that overlay of wisdom onto conservatism and foolishness onto radicalism—especially if we include the political overtones of Left and Right—is untenable.

Don’t trust anyone over 30.

If you’re not a liberal at 20, you have no heart. If you’re not a conservative at 40, you have no brain.

When you grow up, your heart dies.

There’s a long tail to this cultural framework, and I think what JVL mourns and clings to is the framework. It’s a loosely fitting description of the swirling soup of aging and learning and adjustment to the ways of the world, to “selling out,” to gaining a family and property and community esteem in a place — things we are loathe to put at risk through wild-eyed radicalism — to more or less wrapping up a heady phase of experimentation (or social funneling) and individuation to find ourselves, our identities and our places in the world, to settling for this or that kind of life we picture is right or ordained for us for the rest of our days. We give up a lot of the heady dreams and fleeting fancies of youth, including the noble causes that maybe inspired us, and knuckle down to lives of work and family and childrearing and friends, maybe cultivating a hobby or avocation in our spare time.

Nice if you can get it, I suppose. And that process perpetuates JVL’s graphic above: with incrementalism usually winning the day, as most folks cluster around a sensible center, scared off from the radicalism of both right-wing revanchism and left-wing utopianism. JVL wants to rehabilitate and preserve conservatism as a disposition of cautionary wisdom contra wild utopian schemes, but now that revanchism has conquered America, he’s open to being more daring.

He’s beginning to part ways…a bit…with his beloved framework.

On August 13, as part 3 of his Triad column, JVL took us back almost a decade, to 2016 and a piece in Politico by Matthew MacWilliams who found that “a single statistically significant variable predicts whether a voter supports Trump—and it’s not race, income or education levels: It’s authoritarianism.”

As MacWilliams describes them, “Authoritarians obey. They rally to and follow strong leaders. And they respond aggressively to outsiders, especially when they feel threatened”

MacWilliams’ argument is basically that authoritarian tendencies used to be more evenly dispersed between the two major parties. But, pace political scientist Marc Hetherington’s research, they’ve migrated to the GOP, probably due to the Democrats’ embrace of civil rights, gay rights, employment protections, and etc. Now authoritarians cluster in the Republican party, though MacWilliams identified blocs of authoritarians among Independents and remaining Dems.

I was surprised to see JVL veer back almost a decade to a piece “discovering” authoritarianism as the key unlocking Trumpism. I mean, Adorno and Company tackled authoritarianism as a personality cluster back in 1951, and even I was tracking authoritarianism as a big explainer in the Why Trump? debates in 2016. Turns out, a dig through my files revealed I’d read about MacWilliams and Hetherington in March of 2016. (So many names, such declining memory. So long ago, I’d forgotten them.)

So, did JVL just glide over the soul-searching of 2016, the “How could this Happen?” debates, including the endless outreaches to Republicans in rural diners, the arguments about racism vs. economic left-behinds of the “white working class”? To say nothing about the sexism and misogyny on display during the Clinton run? Was he not all that interested in the causes? I can’t say. It certainly seems like the authoritarian thesis is new to him now in mid-2025, but look how he handles it.

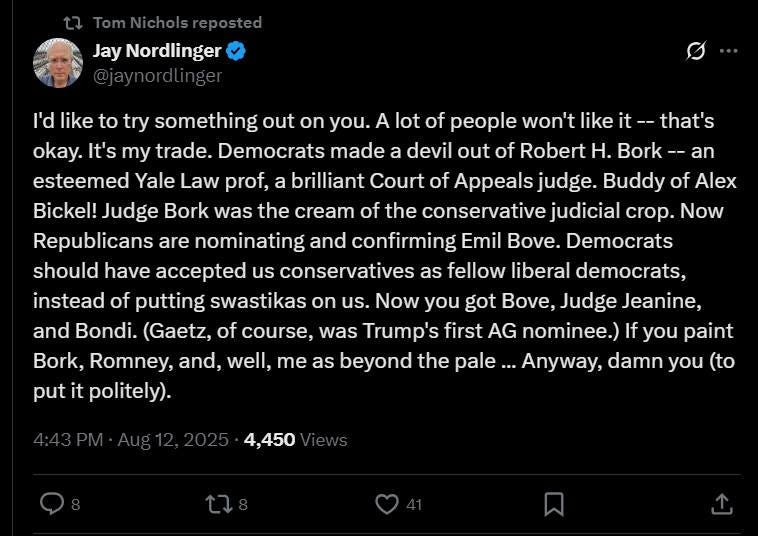

His piece on August 14, “Was Trump the Inevitable Endpoint of Conservatism? A reckoning for conservatives, liberals, and America,” includes a tweet by his “buddy” Jay Nordlinger, which I’d found crossposted on Bluesky that same day, retweeted by Never Trumper Tom Nichols:

Ignore, please, that Robert Bork was a monstrous nightmare. Ignore, please, all the many counterpoints and dunkings on this tweet that are also true and relevant. Do not, however, ignore this well-known rebuttal image:

JVL dissents from Nordlinger’s position in two ways. First, he claims that

This lack of perspective is an American problem, not a liberal or conservative problem. Liberals claimed that Bork bore the mark of the beast. Conservatives swore that Bill Clinton was a socialist who was running a drug ring out of a secret airstrip in Mena. This is what we do in America. We pretend that George H.W. Bush is the worst fascist ever while he’s in politics—and then we revere him when he’s gone. Just like people accused FDR of being a commie and said the New Deal was socialism.

I’ll grant that H.W. looks like a quaint Yankee noblesse oblige figure in hindsight, even to me in some respects, but I was also alive and politically aware during his term, and I can say that the main reason for my relative “softening” on him is the contrasting toxic mutation of every subsequent major figure of the GOP. It also helps that he was a one-termer. But I do consider H.W. as part of a Reaganite and neoliberal era that was relatively defined and discrete and which has been absorbed, twisted and yet also yeeted to the moon in years since, replaced by something far more brazen and open and, yes, fascistic.

As for Clinton, back then I was thrilled to see a Democrat actually win for a change. But as his capitulations and foibles unfolded, his triangulations and Third Way neoliberal centrisms won the day at the expense of what it used to mean to be a Democrat, I soured. He reigned as a Republican in most ways, and that became the basis of my expectations for Democratic presidents moving forward: GOP lite.

But Republican smears and conspiracies not only raged (and what’s more important, they had more force and impact) against him and Hillary, they continued and spread to target any Democratic tall poppy to follow, amping up in intensity and popularity on the right as the years passed. Meanwhile, so many of the Never Trumpers of today signed on to W. Bush’s war in Iraq as I watched the vast majority of Americans go mad and pivot from one groupthink rationale to the next for that mess. W’s theocratic supporters presaged the Evangelical-Catholic elite fusion we see in the post-liberal nat-con and other would-be theorists of Trumpism, and their affinity for Israeli ethnonationalism makes a great deal of sense if you’ve paid attention to the themes and threads and underbellies of conservative ideology for a long spell.

But my feeling is that JVL really hasn’t done this. My guess is that he has taken conservatism at more or less face value and in good faith for most of his time as a writer and thinker, probably across most of these periods. I can’t fault him that much: I grew up believing and then trying to maintain the belief that my conservative Republican fellow Kansans were, at base, just regular folks who happened to disagree on how to achieve the best for our country, that we likely agreed on basic values far more than we ever disagreed. Our means were just different.

I no longer believe that, because I can no longer wear rose colored glasses. Oh, I do believe that many people are under a spell, but that spell had a lot of pre-existing material to work with in the souls of my neighbors. And I watched, over decades, as various actors in prominent positions—from right-wing intellectuals to politicians to radio talkers and cable news jackasses—fed and fed the worst tendencies in my neighbors’ souls to the point where they cheer on Donald Trump and his regime today. Some may be redeemable. Most probably love their pets. Maybe also their children, in some way, as they understand it, but even that’s debatable.

JVL chalks this up to…wait for it…polarization:

I’m skeptical that this crying-wolf effect has much influence on people’s actual behaviors. Why? A couple reasons.

First, voter coalitions are constantly shifting, both in demographic makeup and in the actual humans, who age in and die off. How many presidential elections does the average American vote in over a lifetime? Ten? Twelve? This is not nice to say but the conservatives who were most outraged by the Bork fight died years ago. A large percentage of them weren’t around to vote for Trump the first time, let alone the second and third times.

Instead, Trump was powered by a huge cohort of new voters—many of whom never (or only rarely) voted before Trump entered politics. It’s not merely the case that Trump’s base has no idea who Bob Bork was today—it’s that these low-info mouthbreathers wouldn’t have known who Bork was if they had been of voting age in 1988.

The second reason I’m skeptical that there’s causality is Democratic voting behavior. Over the same period of time nearly every prominent Democrat was made out by Republicans to be a dangerous, radical socialist—yet Democrats did not respond by trying to tear down the liberal order with their own authoritarian version of Trump.

So we ask: Why? Why did the Republican party and conservatism fall to authoritarianism while the Democratic party and liberalism have (so far) resisted it?

I suspect that the answer is not because Democrats and liberals are better human beings. People are people. Instead, I suspect that the answer is idiosyncratic and contingent.

The other day I linked to a Matthew MacWilliams essay from January 2016. MacWilliams had been looking at historical polling data and the work of political scientist Marc Hetherington when he noticed three things:

There exists in America a sizable cohort of voters who are attracted to authoritarian ideas.

Prior to 2008, these authoritarian-curious voters had been more or less equally distributed between the parties.

In 2016 everyone in America who was attracted to authoritarian aspects rushed to embrace Trump.

In one sense this is extraordinary. But in another it’s totally banal: It’s just polarization.

We’ve seen polarization come to define every aspect of American politics over the last thirty years as we sorted into homogeneous parties, geographies, churches, brands, whatever. In the same way that most pro-lifers consolidated in one party and most gay-rights advocates consolidated in another party, so did the people who were interested in authoritarianism.

The trick is just that we tend not to understand “authoritarianism” as though it behaves like any other normal political issue. Maybe we have to do that now.

There are several glib problems here.

First, it’s true that most folks alive today would have to check Wikipedia to even know who Robert Bork was. But not so the Right. On the Right, Bork is part of a Grand Narrative of Grievance Over Evil Underhanded Chicanery Committed By The Left that justifies any and all means in the quest to vanquish the commie socialists out to destroy God, Apple Pie, Baseball, The Virgin Mary, and America as it was meant to be. It’s a just-so story handed down in a vast network of think tanks that serve as feeder leagues to judgeships and sinecures and appointments and other high positions in the right-wing universe of influence. You don’t think Bork and Borking were top-of-mind for the Federalist Society, for the SCOTUS Six? They may not be the mass of voters who backed Trump, but they are his steadfast allies and enablers. There is no comparable counterpart among normie Democrats or liberals. They simply don’t have an ideological indoctrination curriculum like the Right does. As such, Bork is a Lost Cause narrative not unlike the Civil War and functions in the same way for the Right, animating and living on across the generations due to active cultural transmission among the hardest of the hardcore.

That hardcore set drives the GOP authoritarian movement, viewing Dems and libs as irredeemable enemies, funding media to demonize them, movements to disenfranchise them, among the low-info set. New voters glom onto the vibes emitted by the scads of influencers funded and seeded by this movement, and the momentum builds, such that narratives matter more than reality, and certainly more than history.

JVL gets at this, in a way, by noting how all the conspiracies and hyperboles about Democrats as socialist commies out to steal our guns turned out to be bunkum during the same time. The Dems didn’t go authoritarian, but this somehow isn’t due to libs and Dems being better people.

Well, fair enough. Nobody’s feces is free of odor on any given scale of stinkiness. But why didn’t the Dem’s fulfill the prophecies the Right has been proclaiming since the 1930s?

JVL’s answer? Simple polarization. Authoritarianism is just like abortion or gay-rights. Just another “issue” that used to fall more or less evenly across the two main parties and has now sorted itself firmly into one of the two camps thanks to partisan realignments.

This makes the process of “polarization” seem like a natural, ineluctable phenomenon, and this is one of the reasons that many political scientists reject the phrase and the polarization frame with the heat of a thousand suns. It’s a cop-out that not only tells us nothing useful, it, in fact, hides the reality of what’s gone on. Polarization implies that both the left and the right have gone to extremes, leaving the sensible, moderates in the center high and dry, wondering whatever became of compromise and, well, JVL’s incrementalism and sanity. But countless analyses show that it’s the political Right which has gone crazy, while the Democrats have not followed suit.

One reason increasing numbers of political scientists oppose the cop-out of “polarization” as a “both-sides” equivocation for what we’re seeing with Trumpism, is that it betrays their own discipline by abdicating any responsibility to defend or advocate for democracy. It’s the precise move JVL makes here: lumping democracy itself in with other issues (as important as they are) as if parties can simply pick and choose their stances on them and carry on as normal in the American political context. A party going anti-democracy, anti-rule of law, anti-due process, anti-constitution is not merely another staking out of political terrain in hopes of winning over voters at the ballot box; it’s a fundamental rejection of the concept of ballot boxes, at least going forward. Put simply: you don’t get to make authoritarianism a live issue in American politics and treat it as “totally banal…like any other normal political issue.”

JVL is correct when he says that authoritarianism is a live issue in America. He’s correct when he notes that it always has been, but that, in eras prior, it’s been distributed more evenly across the partisan divides. Partisan sorting—a process that’s been underway since at least the Civil Rights-embracing turn by the Democrats in the 1960s, and which took perhaps a generation to sink in for rank-and-file voters, as seen in the Reagan “revolution,”—began with a Democratic embrace of greater egalitarianism, a broader extension of democracy to include the previously excluded, and it “drove” intolerant, racist, sexist, and homophobic Democrats into the arms of the GOP and of the religious Right (which “coincidentally” allied with the GOP).

But this wasn’t a single stroke of lightning that triggered a forest fire. No, the Dems arguably presumed that income and wealth inequality would not skyrocket, perhaps because labor was firmly in their camp, so they took it for granted. The GOP courted socially conservative blue collars and drew them into the Reagan coalition. Dems increasingly tried to compensate for their losses by pivoting to Republican Lite, Third Way, neoliberalism that only made inequality worse and further eroded safety nets, undercutting social mobility and trust in institutions, while piling on against crime and poverty. Meanwhile, the Right leveraged all its money and influence and networks to found think tanks and fund alternate institutions and media empires to pump cynical propaganda into living rooms and the cabs of F-150s preaching about how demonic and feminized the liberals were. In the end, elected Dems wound up largely feckless, skittish, beholden to big donors and lobbies, consultant- and poll-driven, and convinced they had no agency while the press treats them as if they are the only actors with agency while the GOP is an inexorable force of nature.

Or, to put it more simply: Dems embraced egalitarianism more strongly in the 1960s, and the resulting realignment of egalitarians and authoritarians as they sorted themselves into D and R was vastly better recognized, handled, mobilized, and weaponized by the Republicans. Why was that?

Part, I think, is that the Republicans have always been more of an ideological party, while the Dems have been a coalition party. This means the GOP has always been more in touch with the values at its core that serve as throughlines. It’s hard to miss hierarchy as one of those values, including the persistent idea that “some people are just plain better than, more deserving than, others” based on this or that criterion. An entitled individualistic party of wealth and laissez faire, that through the 20th century hated government rules, regs and taxes, bolstered by an infusion of disgruntled racist Democrats and haters of women and queers, could only stomp the gas pedal toward greater authoritarianism.

The GOP as an ideological party sensed its core and drew people who resonated with it to itself. The Dems, as a coalitional party, perhaps developed its egalitarianism—as fitful and abortive and coopted as it has often been—in something more like a process of emergent development. It still doesn’t completely recognize that this is a core part of its ideology, or that it has an ideology. Or values, for that matter.

JVL doubts that Dems eschewed authoritarianism because they are simply better human beings. To some extent, I agree. But I also suspect that JVL downplays the threads of persistent crypto-ideology that wind their way through the two major parties through their various historical turns and evolutions. JVL seems…weak on ideology, dismissive of it, as these entries of his I’m focusing on suggest. He chalks these big turns of the ships up to idiosyncrasy and contingency.

Well, sure. I mean, What if Nixon hadn’t been an asshole? What if he’d eschewed a Southern Strategy because conscience told him it was just wrong? What if both parties had been principled and joined together to stamp out essentialized hierarchies of value among humans? What if they’d done that post-Civil War? A butterfly lands on the nose of Strom Thurmond, revealing to him the beauty and awe of all life, and somewhere a neo-confederate hurricane is averted?

As for “better human beings,” well, the future of a “polarized” or authoritarian-sorted landscape of American politics makes for a world where, yes, Dems will simply be better people. JVL’s own corpus of writings—especially his Leopards Eating Faces entries—supports this. Even if we grant that the GOP went authoritarian through some ineluctable, “natural” process of sorting (which I think is nutty—”we didn’t do nuthin’…these racists and supremacists just showed up!”), the longer it continues this way, the more we should be able to say that good people are not Republicans or “conservatives.” This won’t mean that every Democrat or liberal is, therefore, a good person, but it probably will increase the odds that the average Dem or lib is a better person than the average Republican or con.

Unless, of course, you go completely value relativist on the whole question of authoritarianism, supremacism, fascism, and related indicia—and we’re back to why political scientists object so strongly to the “polarization” framework and explanation.

In short, JVL looks at the work of Matthew MacWilliams on authoritarianism and declares that fascism is an American problem, not specifically a “conservative” one. In theory, the Left could have gone authoritarian. It could have elected a Stalin and seized guns and collectivized the economy.

Thing is, it didn’t.

A million things maybe prevented that. The political Right may have prevented that. Moderates and centrists may have prevented that. Clinton and neoliberals may have prevented that. FDR’s “saving capitalism” may have prevented that. We can’t rerun history and remove various elements to see which, if any, was the determinative factor.

But this notion that the Left (or just Dems and liberals, for they are not the same) would have led, lockstep, to a Stalin, is itself, childish. It presumes mechanistic, determined plodding to inevitable ends: Hitler or Stalin. Surely, a good decade almost of debates about the F-word in academia and pundit-land have taught us a few things about the nuances around “fascism” vs. “authoritarianism” vs. “competitive authoritarianism” and all the other near-synonyms. Things do not recur identically. History doesn’t repeat, but it does rhyme. Fascism wasn’t supposed to happen absent a strong Left, but all we had was Bernie Sanders. Then again we also had a Big Lie and lots of Little Lies propagandistically blown up all over right-wing media for decades, demonizing the Left as an omnipresent threat to all we hold dear. Does that suffice? A fake threat from the Left? Seems like it does, given what we’re seeing.

For all his both-sides talk of how H.W. Bush was supposed to be a fascist, according to the left, that talk was never broadcast anywhere as loudly, as ubiquitously, as effectively, as what Rush Limbaugh was pouring into the ears of millions of future Trumpists about how evil Bill and Hillary, then Kerry, then Pelosi and, and, and, and….all were. There’s similar rhetoric and charges, but then there’s a chasm of difference in range and scope and impact and influence and what’s viewed as legitimate discourse on each side.

Behind all this JVL psychologizing, for me, is something more important and subtle than just dunking on a writer I really like.

My point is that below ideology is a theme, a recurring motif, a hint of a worldview. And on the Right, it’s been hierarchy and its corollary: the disposability of those low enough. Poor, foreign, ill-fitting because of race or gender or creed or sex, at least if they forget their designated place. Dissenters of all kinds. The different.

Against this strain of exclusion has been a liberatory or at least live-and-let-live spirit of empirical reality that said people are people, that held up a more creedal Americanism, that valued dissent, that saw disposability as wrong at a moral level. It may have been badly articulated by Dems or liberals, and sometimes Dems and libs joined in the chorus of the Right to exclude and demonize, and it’s been co-opted by charities and NGOs in professionalized and state-dependent bureaucracies (which now prove especially vulnerable to Trumpism 2.0)—but those attuned to the music have long known which side was less evil at basic, thematic levels.

So how could JVL miss this theme? I think he has, obviously. Most of his pals at The Bulwark are former Republicans. Jay Nordlinger—whose tweet imagining capitulation in the 1980s on the Bork nomination is JVL’s “buddy.” So I think his crowd is generally right-of-center, or has been over the years. He’s a hard science guy and likes to crunch numbers. A normie Catholic from New Jersey, a comics nerd, a watch guy, whose kids do sports. He strikes me as, basically, a grounded, empirical, fairly blunt-speaking realist in a lot of ways, even when he ponders scenarios like de-nazifying a post-Trump DOJ or advising the Dems to sit on their hands and let Trump run wild to teach Americans what it means to have voted for this shitheel.

I just don’t think JVL has spent a lot of time thinking or reading deeply about political theory, ideology, and the psychology behind it, frankly. There’s his recent discovery of the MacWilliams thesis, which is really an update of Adorno from 1951. These kinds of questionnaires are based on childrearing questions. MacWilliams: “whether it is more important for the voter to have a child who is respectful or independent; obedient or self-reliant; well-behaved or considerate; and well-mannered or curious. Respondents who pick the first option in each of these questions are strongly authoritarian.”

Back in 1996, neurolinguist George Lakoff’s Moral Politics: How Liberals and Conservatives Think, posited that all thinking happens in frameworks, that these frames are metaphorical in structure, and that the key way to think of political differences in the US is to focus on the metaphor, “The nation is like a family.” In that metaphor, the kind of family matters a great deal, with conservatives believing the family should be headed by a Strict Father figure, while liberals preferring a Nurturant Parent. For Strict Father, read authoritarian. Lakoff claimed his book started with the question of what to do with a crying baby: let it cry or go it it in the night?

It’s an argument that’s strongly tied to the basic insight of 1983’s seminal For Your Own Good: Hidden Cruelty in Child-Rearing and the Roots of Violence, by pioneering psychiatrist Alice Miller. She looked at authoritarian, even cruel, prewar European child-rearing advice and argued that it shaped the trajectories of figures like Hitler. Go read Talia Lavin’s Wild Faith: How the Christian Right is Taking Over America, and you’ll connect a lot of dots between authoritarian parenting and the literal legions of present-day Christian nationalists, while at the same time giving you nightmare fuel for the rest of your days.

This stuff isn’t new, and it’s not ideology in the sense of small government and low taxes, per se. It runs deeper than that. It goes to basic worldviews of hierarchy and dominance, of fundamental worth and entitlement to power. As the Lakovians say, men over women, parents over children, rich over poor, straight over gay, cis over trans, white over non-white, and so on. If JVL has been focused on the parts of the iceberg above the water, the public-facing, good-faith-presenting stated views of political parties and movement ideology, it’s not strange that he has underappreciated the ur-motives and drivers of “conservatism” all this time, but the evidence and the research is and has been out there.

JVL’s August 15 entry followed up on the discussions his readers offered regarding his lightbulb moments on authoritarianism and conservatism. Here again, he confessed surprise at something that isn’t all that novel, though it’s only come to light since the rise of Trump for the most part. He quotes a commenter:

People tend to forget what U.S. conservatism was prior to 1945. Before that point, the U.S. right was openly pro-fascist. We even had an attempted fascist coup in the business plot. After the war, with the full horrors of Nazi Germany on display, fascism had to move underground. . . .

[B]etween the pressure to disavow Nazi horrors, and the need to present a good face in opposition to the USSR, conservatives picked up liberal imagery and ideals. They talked about individual rights and small government (even if they didn’t really mean it).

But now that the horrors have faded, and the Soviet threat no longer exists, the true conservatives can come back out of the woodwork. This is what conservatives have always been, what they have always wanted. Since the US has never had a monarch for conservatives to champion, we get the alternative, an idealized version of the “nation,” narrowly defined, with an all powerful leader at its head to enact the will of “the people.”

Aka. Fascism.

This is the basic “Continuity” thesis, and I wrote about it back in March of 2024:

The F-word debate isn’t alone. There’s another pundit and scholarly debate afoot, and it’s about whether or not Trump represents a rupture in conservatism and the GOP, or whether he signifies continuity, as in “it was always going to end up here sooner or later.” The Left, predictably, tends to come down on the latter side. And I think they have the stronger argument than the rupturists. Call it the C-Word debate: for Conservatism, Continuity or Crackup?

The idea that the entire Cold War was basically a huge interregnum in America’s worldview battle between fascist hierarchs on the Right and egalitarian-leaning folks more leftward (I’m not going to paint them as more saintly than they were) is new-ish, but not that new. Again, I’m surprised JVL had to learn about it from a commenter. He has access to interview some of the best and brightest folks around, from scholars to authors to historians to you-name-it. And shoot, he’s probably got way more disposable income than I do to buy their books and access their paywalled articles and read their arguments than I do, yet I’ve read enough of it to be convinced, despite my vastly reduced reading time thanks to scrubbing toilets and mopping floors 40 hours a week.

I mean, the argument isn’t all that hard. It just flies in the face of the conventional story we’ve been told for my whole life:

External enemies tend to unify a fractious public. And radicals [in this case, the far right authoritarians and fascists who’ve always been part of the “conservative” coalition] always need some kind of entryism and legitimation into the mainstream. So the Cold War against communism and the Soviets was ideal. They even called it the “liberal consensus.” It wasn’t a period of comity and bipartisanship or some end of ideology. It was a temporary respite or domestic ceasefire (although throughout, the Right always portrayed the left and Democrats as weaker and suspect as regards Communism and international threats). Yet even during this period, the Right was moving more anti-democratic, with the Southern Strategy, courting and capturing the religious right, leveraging the wealth of billionaires to establish and lavishly fund alternative infrastructures of media and academia and other power centers. Once the Cold War was over, the Right had achieved mainstream status and even infiltrated and taken over the Republican party. Partisan sorting had been accomplished along the unspoken lines of hierarchy and dominance that had always been implicit. It was time to start pushing the accelerator.

This is the same sort of myth-busting for conservatives to cope with that liberals have to accept when it comes to the Supreme Court. We were raised on noble stories of Brown v. Board and Miranda and Loving, so we got this notion that the Court was a force for justice and egalitarianism. But the Warren Court era, was an aberration, an exception to the long historical track record of the Supreme Court. Courts in general are conservative, not avant garde leaders of expansions of rights and fairness, at least in the United States. But a whole generation or two got it into our heads that SCOTUS was a great and noble institution that could be relied on to vindicate our rights, and we are repeatedly shocked and searching for copium whenever they display their sudden but inevitable betrayal.

By the same token, conservative mythology—promoted strongly by the gatekeepers of movement conservatism itself and only fairly recently questioned by historians—has been highly sanitized and glossed. You’re absolutely not going to encounter the thesis that the ur-ideology underlying conservatism as a political force is authoritarian domination of those deemed less-than, interrupted only by a long time-out, if you accept the standard tale or interact only with run-of-the-mill Republicans. Run-of-the-mill Republicans themselves have no reason to know it: they’ve either been schooled in the noble official history or just view being a Republican as a set of policy preferences and the vibe of the Chamber of Commerce set. You’re going to have to dig, or else be semi-obsessed with the question of why people you were told are basically decent keep aligning with a party and a worldview you see as sliding further and further into evil.

JVL concludes his last entry on this theme—third in a kind of Triad, you could say—with these words:

I can’t answer this question, but it’s something I’m going to chew on for a long time. People naturally assume that the intellectual paradigms they are born into are the default state. But that’s not necessarily true. Why couldn’t it be the case that “modern conservatism” as it has euphemistically been called—meaning conservatism as it existed in the Republican party from roughly Eisenhower to the Bushes—was a temporary aberration? What if True Conservatism was always the blood-and-soil view that dominated the American right before the Cold War?

What if Trump isn’t a fulfillment of “modern conservatism,” but the book closing on that errant period and conservatism returning to what it has traditionally been in American history?

I shake my head. This isn’t that radical of an idea. It’s only crazy if you’ve not done the reading. And JVL has access to pretty much all the people who make this argument with stronger credentials than Reddit commenters and way more amassed evidence. He just hasn’t been attending to their work.

I know: he’s focused on a lot of other things, looking through lenses at different scales of magnification. He’s the editor at The Bulwark. He does a daily podcast and writes a column several times a week. I guess they do tours. They try to create a kind of pro-democracy digital community of readers.

But his work, and that of The Bulwark in general, is to counter authoritarianism and the destruction of democracy. That they are composed of a lot of ex-Republicans and conservatives is, in some ways, good news, but without this kind of deep reckoning that’s anything but harebrained, we could well win against Trumpism and authoritarianism (though the odds are bad absent such an understanding) only to recapitulate it later because the essence of the moral rot is left unexamined.