Fifteen, sixteen years ago, I used to go on day trips with a dear friend to take pictures of obscure, often declining rural areas. The photo banner on these Substack entries is a picture I took in a place called Grinnell, Kansas.

Here are some more.

In a lot of these places my friend and I went we’d meet a local who’d gesture and tell us that Main Street was once home to three multistory creameries—there, there, and there—among other local businesses. We’d stare at the complete absence of, well, anything today and try to picture it all, both believing our local source, yet finding it impossible to believe, given the dearth of any sign that this place had ever been anything but empty.

The explanation usually involved the demise of railroads and the rise of the Interstate highways, or the consolidation of schools and farms that drew folks to jobs away from small towns until they just…dried up for the most part.

Yet they are still around. And my buddy and I would visit them back in ‘09 and ‘10 to snap photos.

It’s fair to say we loved the details, usually nothing larger in frame than a single room. I was drawn to gadgets and old contraptions, doorways and windows; my pal to tight-shots of textures almost completely decontextualized sometimes because he’s more arty than I am.

I did a lot of thinking in those days about our hobby. This was when such photos were having a moment, I gather, under the derisive name, “ruin porn.” I felt like we were documenting places too late in their lifespan, but documenting nonetheless. Historical societies might have sepia-toned photos of the towns’ heydays, but who had pictures of what had become of them inside, shot through broken windows, with crumbling furniture and antiques long beyond salvaging under collapsed ceilings? That was part of the life cycle, too, part of the story. A sad part, but worthy, in the name of dignity, of being recorded. Everybody shoots the prom queen on her big day, but how many photograph her wrinkles, her thinning hair, her walker, her oxygen tank when she’s mostly mute in the nursing home?

Intimations on mortality. Records of artifacts and ingenuity and endurance and places where people once were. Something about the interplay of culture and nature, the inexorability of the latter and the imperative of maintenance and effort required by the former.

Communities require effort to live. Nature just waits to reclaim the spaces when that effort ceases, through the death or absence of the humans.

But nature isn’t always patient.

On Sunday, May 18, tornadoes manifested seemingly all over the obscure parts of Western Kansas.

If you don’t know much about tornadoes, think dry, land hurricanes. The good news is no storm surges, and in terms of power and size, they can vary toward the small scale more easily. The bad news is that you don’t get several days of warning to evacuate an area or board up homes in anticipation of a well-forecast tornado veering in. You can be driving down the road and see one appear on the horizon, and then you have to…deal.

If you’re stationary—someone who lives in one of these rural western Kansas towns, for instance—you pay a lot of attention to the weather forecast, hope, and pray.

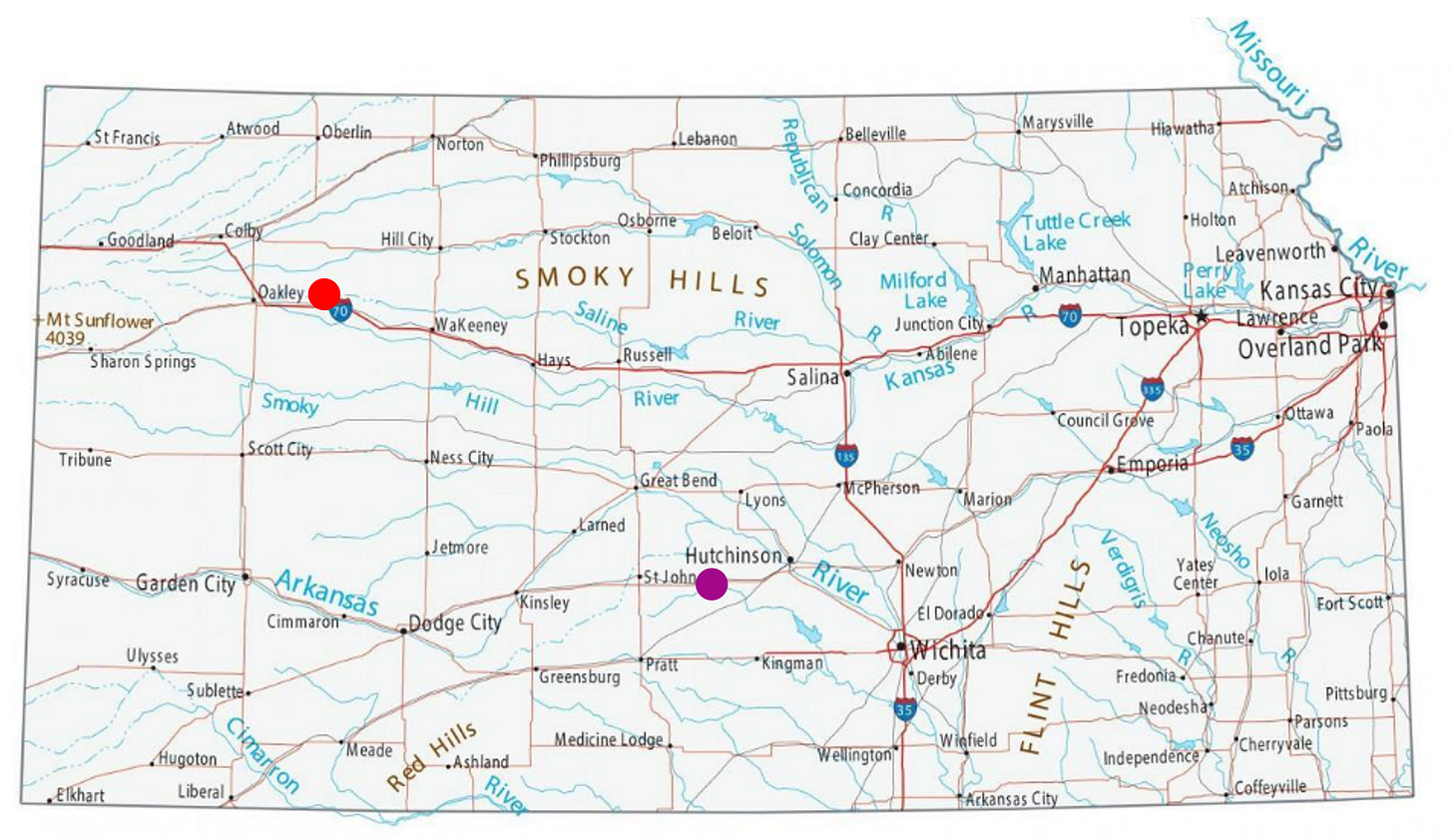

The prayers worked in Kansas as far as I’m aware. No lives were lost, despite tornadoes hitting the small towns of Plevna in Reno County or in Grinnell in Gove County. For a traumatic few minutes, a tornado threatened the town of Greensburg in Kiowa County, which in 2007 was almost literally obliterated by an EF5 twister that killed eleven and ended up driving away half the population over time. This time, Greensburg was spared.

Grinnell got hit, at least the western part, which doesn’t sound so bad (“just the western part”) until you learn that there are only about 260 people living in Grinnell. Eleven of those people are family to me. Cousins and aunts and uncles to my kids. I cannot count the number of trips we’ve made to that tiny town over the decades for family get-togethers, birthdays, anniversaries, funerals, baptisms, weddings, and so on.

All the Grinnell folks are safe and alive, as I said, but the town is largely wrecked. Per my sister-in-law, her house is not great, but standing. The windows are all blown out, something punched through the wall of her daughter’s bedroom, and a neighbor’s outbuilding is now in their yard, but last we heard, the house is upright and habitable.

The house my wife’s parents lived in most of their time in Grinnell, the house our kids knew as Grandma and Grandpa’s, is a loss.

Here’s probably my favorite picture of our daughter as a little, in the living room of “Grandma and Grandpa’s house,” the picture window behind her, she so fierce and sassy, such a happy memory of those years.

Here’s what that house looked like Monday:

The current owner, whom I would describe as shell-shocked, shared a video with KAKE News on Facebook.

Now a house is, yes, just a house. And human lives are infinitely more precious. And no lives were lost this Sunday. Even the candles in the Catholic church remained burning, despite the roof of the sanctuary having been ripped off and deposited down the way.

But the objects, the structures, the artifacts of human culture we make and build and use and inhabit take on, absorb, represent, emanate meanings and memories and moments. Scrapbooks of the built environment, even if they’re humble or lowly. Nothing special about any one thing perhaps, no grand gothic architecture to preserve and enter into historical registries, but significant to the texture of people’s lives all the same. And when it’s just…gone…it hurts in a way you’re not supposed to make too much of a fuss about—no one died after all, and that’s the important thing, right?—but there’s still a mourning, and it’s right to mourn.

And it’s a material blow to a community, no matter its size. For a community as small as Grinnell, population 260 in 2020, it’s a big one. Like so many tiny places “in the middle of nowhere” it was already working hard to maintain itself amid the forces of culture and nature that threatened before the tornado hit. And now, well, wow. Talk about having their work cut out for them.

So I’m asking y’all: please help.

I have only a measly 191 subscribers to this free Substack newsletter. I have never set it up for paid subscriptions and don’t ever plan to. I’m not a writer-writer. I’m a janitor. I work too hard at my paying gig to make the time to craft quality language here, the kind I envy in real writers. I think money should go to folks like that, or to subject matter experts or to reporters who dig up facts from sources thanks to hard work and shoe-leather, real and/or digital.

But if each subscriber could pitch in $5 to help rebuild this little town that’s not going to get headlines or press outside Kansas, whose story will fade out in a matter of days, I could help them raise about a grand, and that ain’t nothing. Every little bit helps.

I rant and rave here about global issues and the injustices to folks around the country and world, big-picture problems like democracy and the rule of law and fascism and empathy. And yeah, I admit straight-up that this hits me hard because four percent of the population of this town is family. (Pretty much the rest of my wife’s family lives just down the road from Grinnell in towns like Oakley and Colby, so they didn’t get hit, but basically by, like, a stone’s throw, geographically speaking.)

But if there’s anything that unites human beings, it’s vulnerability and frailty. It comes for us all at some time or another. Happenstance, bad luck, bad choices, random, freak events, illness, aging, infirmity, disability, mortality. The flesh is heir to these things. That’s what unites us, our finitude and our fragility. Beneath everything, this is what makes us the same.

If you’ve got the means, please contribute more if you can. And pitch in some money for Plevna or any other town affected. Folks in Kentucky lost their lives to the tornadoes there. St. Louis got hit.

There’s no shortage of need in the world. I’m just trying to put out a call for this one little place and asking for a cup-of-pricey-coffee if you can swing it. Not for me, not even for my relatives, because they escaped the worst of even the structural damage from what I have heard. Their neighbors, though. Whew.

If you could share this entry along the line, it might even reach a few more people and maybe generate a few more fiskies for the folks out there.

I’d sure appreciate it.

https://gnwkcf.fcsuite.com/erp/donate/create/fund?funit_id=1236

A Note about the Goat:

The above picture of the goat says something about small towns. The story, as I remember it, speaks to the way a small town’s residents can half-despise one another and fight and snipe, but still manage to pull and work together when they need to because they almost always need to. When your population can all fit inside the school gymnasium, you really can’t afford that many free riders or long-standing feuds. You have to find a way to get along, no matter how much you hate somebody’s politics or attitude or whatever.

Makes me think of The Decemberists song about the Speculator Mine disaster of 1917

Get the rocks in the box

Get the water right down to your socks

This bulkhead's built of fallen brethren bonesWe all do what we can

We endure our fellow man

And we sing our songs to the headframes' creaks and moans

So there was one guy who wouldn’t cut his grass. The town leaders repeatedly told him to, but he didn’t. As the warnings escalated and maybe got legal and fines were mentioned, he decided to get goats to keep his grass nibbled down instead of mowing. I think the idea was to comply maliciously by, I don’t know, making the town look even more bumpkinny than it was, with live goats grazing instead of capitulating to some town council image of neatly manicured lawns?

Curmudgeon? Local independent hero? Pain in the ass? Show-off? Psycho-libertarian? Guy who can’t pick the right hill to die on? Who knows? Definitely a character. And definitely entertaining dinner table stories.

We endure our fellow man.

Because we need one another to make this collective effort work.